Giuseppe Verdi – his BIOGRAPHY and his PLACES

Giuseppe Verdi – a biography in words and pictures.

The places where Mendelssohn worked and the most important people in his life.

Biographical timetable (click to view)

YOUTH IN LE RONCOLE AND BUSSETO

Verdi grew up in the hamlet of Le Roncole outside Busseto. He was educated in Busseto, where he was encouraged at an early age by his future father-in-law, Barezzi.

Antonio Barezzi:

He went to school in Busseto and stayed there for a few years because he was rejected at the Milan Conservatory. At the age of 23 he married the daughter of his patron Antonio Barezzi and at 25 he left his native land with his wife Margherita, but only 2 years later disaster struck him when illness and childbirth took his wife and two small children. After a huge crisis Verdi could regain his composure with the triumphant success of nand at the age of 32 was able to buy a beautiful residence in Busseto (the Palazzo Orlando in today’s Via Roma), but the people of Busseto did not approve of his partner Giuseppina Strepponi at all and thus drove the maestro first to Paris and later to Sant’ Agata.

After a huge crisis Verdi could regain his composure with the triumphant success of Nabucco and at the age of 32 was able to buy a beautiful residence in Busseto (the Palazzo Orlando in today’s Via Roma), but the people of Busseto did not approve of his partner Giuseppina Strepponi at all and thus drove the maestro first to Paris and later to Sant’ Agata where he spent the rest of his life.

Birthplace in Le Roncole

When you visit the parental home Verdi, you notice the stately size of the house, in no way gives the impression of a mouse-poor family. The house is carefully renovated and left in somewhat original condition.

Verdi’s birthplace:

http://www.casanataleverdi.it/en/

Villa Verdi / Sant’Agata

A few kilometers outside Bussetto lies the stately Sant’Agata estate, originally a farm, converted by Verdi into a residence. He bought the land in 1848 and gradually extended it, with the aim of retiring there at the age of 60. He lived there from 1851 until the end of his life in 1901 with his wife Giuseppina and composed many of his works. He was protected there from the hostility of his compatriots (see the excursus on Traviata below) and appreciated life as a “peasant,” as he called himself.

Villa Verdi is an outstanding place to visit, which, although a museum, has been left as Verdi had left it in his will. It is cared for by his descendants and impresses with a wide variety of exhibits, ranging from the fortepiano to the carriage stable and the death mask. A beautiful park invites you to take a walk.

It is possible that the museum is closed for renovation when you read these lines. Please check before visiting.

Villa Verdi in Sant’Agata:

Teatro Verdi

The neat little theater (with 300 seats) was built during Verdi’s lifetime. Verdi donated 10,000 lire out of courtesy, but never entered the theater out of resentment against the people of Busseto (see excursus below on Traviata). Performances are rather rare, Toscanini even conducted here in honor of Verdi.

Book a guided tour in advance to see the beautiful theater.

Teatro Verdi:

http://www.bussetolive.com/en/poi/verdi-theatre/

CAREER START IN MILAN AND TRIUMPH WITH NABUCCO

Throughout his life, La Scala in Milan was Verdi’s most important artistic reference point. The premiere of his first opera (Oberto) took place in this theater in 1839, and 54 years later also that of his last opera (Falstaff). In addition, the offices of his lifelong publisher Ricordi were located in Milan.

His career really took off at this theater with the sensational success of “Nabucco” in 1843, whereupon the impresario Merelli offered Verdi a contract for a follow-up work. The contract was completely worked out, with only a gap in the compensation sum. Merelli, the impresario of La Scala, asked the composer to insert the sum he liked himself.

The existence of the opera “Nabucco” is inconceivable without the then director of La Scala, Bartolomeo Merelli. He put his trust in Verdi after the failure of his second opera and provided him with the libretto for “Nabucco”. On the one hand, he believed in the young, 26-year-old Italian, and on the other hand, he was looking for new composers, since Bellini had died a few years earlier, Rossini had stopped writing operas, and Donizetti had left for Paris. Verdi was at this time in a deep personal crisis. Within a short time his family had died away. His wife Margherita died at the age of only 26 and their two children were carried off by an epidemic. In addition, his second opera was a failure. Verdi contemplated giving up writing music. What followed was later described by Verdi himself: Merelli had stuffed the libretto into his coat pocket, and when he arrived in his room he threw it on the table. The booklet fell on the floor and it opened just at the point of “Va, pensiero sull’ali dorate”. Verdi’s eyes fell on this passage and he was electrified. That same night, he read through the libretto (this account of Verdi’s is not believed by many historians, but it is nevertheless printed here according to the motto: “Se non è vero, è ben trovato”).

Teatro alla Scala

Seven of Verdi’s operas were premiered at La Scala, but between the first performance of “Giovanna d’Arco” and “Otello” there was a gap of 42 years during which Verdi premiered in Venice, Rome, Naples, Cairo, Florence, Trieste and Paris. Often the reasons were of financial nature, but again and again the new works quickly found their way to La Scala, which remained Verdi’s artistic benchmark throughout his life. Verdi always attached great importance to audience success. His career really took off at this theater with the sensational success of “Nabucco” 1843.

Teatro alla Scala:

https://www.teatroallascala.org/en/index.html

VERDI AND THE CHURCH

Verdi and the church using the opera “Nabucco” as an example

Zaccaria, the high priest of the Hebrews, takes on a weighty role in Nabucco. Reason enough to address the subject of religion in Verdi’s life and operas: “Giuseppe Verdi and religion – that’s a difficult chapter. The great opera composer did not care much for the church. ‘Stay away from priests,’ he once advised his cousin. For his funeral, he forbade himself the presence of clergymen. His longtime companion and later wife, Giuseppina Strepponi, described his attitude by saying, “I wouldn’t exactly say: ‘atheist,’ but certainly not a convinced believer. Nevertheless, Verdi practiced what Christians call charity. The composer also more than earned his merits as a benefactor. He supported needy workers and farmers, he financed an education for children from poor families. He donated the ‘Casa di Riposo’, an old people’s home for singers and musicians in Milan that still exists today; his tomb is also located in the house. Verdi also ran a hospital set up at his expense – where priests were allowed access only for valid reasons.” (Michael Krassnitzer, orf.at).

WORLD SUCCESS WITH THE TRIOLOGIA POPOLARE

The Lagoon City had the honor to premiere two of the greatest Verdian operas at the Teatro la Fenice, the “Traviata” and the “Rigoletto“. One of them became an announced fiasco and the other a surprising triumph. There were only two years between them.

Verdi already suspected in advance that the premiere could end in a fiasco. The choice of subject matter was a tremendous sensation, because until then Italian opera had only known historical subjects. With the contemporary “Traviata” it had arrived in the present for the first time. While kings and knights were the villains, Verdi took the risk of making a courtesan a heroine and holding up a mirror to Italian society. The “Teatro La Fenice” made this situation even worse by setting the action 150 years back into the baroque era, thus taking waltz music ad absurdum. In addition, there were casting difficulties because the opera was scheduled at short notice. Bitterly, Verdi had to admit at the premiere that it “La Traviata” only failed, but that people laughed at it as well. One of the reasons for the fiasco of the premiere of «La Traviata» could have been the corpulence of the leading actress. She did not give the impression of an emaciated woman in the death scene of the third act, provoking laughter from the audience. One newspaper critic sardonically wrote that she was «as fat as a mortadella from Bologna».

The success of the third opera of the Triologia, the “Trovatore,” was immense. Already the premiere on January 19, 1853 in Rome was acclaimed. Applause broke out after each aria, and the end of the third act and the entire fourth act had to be repeated. The opera was also considered novel, despite its more traditional formal structure. In the years that followed, Trovatore was seen throughout Europe and in America. In 1862 Verdi wrote in a letter that “Trovatore” could be heard even in Africa and India. Even today, it is one of the most popular operas, although demand is greater than supply due to casting difficulties.

Teatro la Fenice

This glamorous and beautiful theater is of course mighty proud of the premiere of these two operas by Verdi. When it was restored to its former glory after a deliberately set fire (an attempted cover-up by those responsible for the construction), it was then reopened with Traviata in 2004. This theater shines with its acoustics, its beauty and the excellence of its performances. A visit to this theater is a must during a visit to the city, and a guided tour of the theater is also worthwhile.

Teatro la Fenice:

https://www.teatroallascala.org/en/index.html

The story of “Traviata” is based on the novel “The Lady of the Camellias” by Alexandre Dumas. As a young man, Dumas himself lived with Marie Duplessis, a well-known socialite. The latter died of consumption at the age of 25 and Dumas took her as a model for the protagonist of the novel. When Verdi first came into contact with Dumas’ novel, he was deeply moved. It reminded him of his own situation with his partner Giuseppina Strepponi. When he moved in with Giuseppina many years after his wife’s death, Giuseppina was already 32 years old and a woman “with a past.” She was not a courtesan, but had three pregnancies with different men in addition to her professional life as an opera singer. Verdi and Strepponi were harassed by posh society in Paris and retreated back to Verdi’s home. In Bussetto, the couple encountered open resistance from the small-town population. It was particularly painful for Verdi that his former patron and sponsor Barezzi openly opposed him. It is quite possible that Verdi was creating a portrait of Barezzi with the role of Germont (which he had upgraded from Dumas’ original). Two years later, the two moved on to the countryside of Santa Agata. There the compositional history of “Traviata” began.

Giuseppina Strepponi:

ON THE WAY TO MUSIC DRAMA

With “Simon Boccanegra” Verdi took a big step in his music-dramatic conception. In his conception of music drama, Verdi treats each scene as a dramatic and musical unity. The division between recitative and arioso passages becomes fluid. The orchestra gains in importance, Verdi increases its expressiveness and gives it more presence, at the expense of vocal bravura, which many a theatergoer misses in “Simon Boccanegra.” To get to the point of how consistently Verdi was willing to implement his concept of musical drama, the fact that the main character was not assigned a classical aria, which the general public never really wanted to appreciate, lends itself well. Verdi consistently continued on the path to musical drama that he had begun 10 years earlier with “Macbeth”. Surprisingly, Verdi had taken a step back again after “Macbeth” and had subsequently written 10 classical number operas in feverish labor, including his “Triologia popolare”, until he resumed this path with “Simon Boccanegra”. “Simon Boccanegra” was followed by another classical number opera, “Ballo in maschera”.

PARISIAN YEARS AT THE GRAND OPÉRA

Paris meant an important period of Verdi’s life. He often stayed in the French capital, among other reasons to meet his future wife Giuseppina in 1847, later for his opera projects, of which he wrote the “Vêpres siciliennes” and “Don Carlos” for the Paris operas, other works were given French versions (including “les Trouvères” and “Macbeth“). Verdi was at times obsessed with conquering Paris and replacing Meyerbeer as the “opera god” in Paris. His first attempt was “Vêpres siciliennes”, in which Verdi personally took care of the staging and in the process cemented his reputation as a theatrical tyrant; soon he was only called “Merdi” behind closed doors at the opera by the (unpunctual) french musicians.

After Meyerbeer’s death, he was commissioned to write a work for the Grand Opéra during the 1867 World’s Fair. The effort for the “Don Carlos” was gigantic. The fact alone that the theater had to sew a staggering 355 costumes for the premiere is proof enough.

Verdi’s relationship with the Parisians was divided. Early on he was awarded the Legion of Honor, but he refused to take part in the procedure, calling it a muck, which was resented by the Parisians. In the 1950s, Verdi also had two sensational lawsuits with the French national poet Victor Hugo over the rights to perform the operas Ernani and Rigoletto, which were based on the Frenchman’s works.

Success came rather late and Verdi, at the age of over 70, accepted the award of Commander of the Legion of Honor and even dined with Napoleon III and Eugénie in their Compiègne castle.

Paris’ Opera Houses

Unfortunately, the historical Verdi cannot be experienced in Paris, all the opera houses have been burned down or demolished, nevertheless his music is very present in the four opera houses.

Opéra de la bastille:

https://www.operadeparis.fr/ (Palais garnier, Opéra de la bastille)

https://www.chatelet.com/ (Théâtre du Châtelet)

https://www.theatrechampselysees.fr/

TRIP TO SPAIN

Verdi used two historical Spanish subjects for the two Paris operas “Don Carlo” and “La forza del Destino” and drew inspiration from a long trip to Spain.

When Verdi visited the Escorial in his great 1862 trip to Spain, he was impressed, but said in a letter, “I don’t like the Escorial (forgive me for the blasphemy). It is a mass of marble, there are very rich and beautiful objects inside … but the whole thing lacks good taste. It is austere, terrible, like the grim ruler who built it”.

El Escorial

The touch of the Inquisition gripped him and five years later he remembered again when he composed for his “Don Carlo” the great scene of Philip in his lonely chamber of the fourth act (see musical digression below). Verdi saw the king’s small room with a view of the altar, which the king had furnished spartanically, although Philip had expanded the Escorial as a representative seat of power, which had previously been a small nest (Escorial = Spanish for rubble heap). He did not leave his seat of power after 1559 and became increasingly lonely, plagued by illnesses, defeats, state bankruptcies and finally the death of his fourth wife. He died in 1598 in his small room.

Philip II. study in El Escorial:

http://monasteriodelescorial.com/

El Escorial:

Sherry Bodega Gonzalez Byass

On his great trip to Spain in 1862, Verdi also visited Andalusia and went to Jerez with his wife Giuseppina. He visited a Jerez production there (probably Gonzalez Byass) and bought himself a little souvenir in the form of a barrel of sherry!

20 years later, he recalled the trip when he wrote his last work, Falstaff. Falstaff’s very first word is: “Oste! Un’altra bottiglia di Xeres” (Host, another bottle of sherry!).

The producer Gonzalez Byass in Jerez:

https://www.gonzalezbyass.com/

Verdi had a kind of love-hate relationship with Naples. Love connected him with the Neapolitan way of life and the local friends like the librettist Cammarano and the confidant Sanctis. Contempt associated Verdi with the representatives of the kingdom, who made his life difficult with their policies and the censorship of his operas. Paradoxically, Verdi, a republican, wrote a hymn for the Neapolitan Bourbon king as late as 1848; no one knows what devil was driving him, perhaps simply Mammon.

Verdi was at times at war with the theater management of the Teatro San Carlo, which had a difficult relationship with his librettist and friend Cammarano in particular. The theater’s regulations were eons long as to how an opera had to look. Thus, Luisa Miller became Verdi’s last first performance opera for Naples, he had to move the “Ballo in maschera” to Rome for censorship reasons, and later he shifted his attention to Paris and Milan. However, the public remained loyal to the northern Italian and the Aida productions of 1873 and later Otello became great triumphs.

Later he came to Naples several times in winter to spare Giuseppina the winters of Busseto. When Verdi began an affair with the soprano Teresa Stolz, it led to a deep marital crisis. Eventually Giuseppina accepted the situation and the three even spent a vacation together in Naples.

Teresa Stolz:

Teatro San Carlo

When traveling to Naples, it is worth visiting the Teatro San Carlo, it is one of the most beautiful theaters in Italy, if not the world, especially the royal box is impressive. You can join a guided visit and sit in the royal box and feel like a king for a short moment.

View into the auditorium of the Teatro San Carlo with royal box:

https://www.teatrosancarlo.it/

AIDA

Verdi was almost sixty years old when he wrote Aida. He wanted to retire, but was asked by the Viceroy of Egypt to write an opera for the opening of the Cairo Opera House. Verdi then, to turn down the request, named an outrageously high sum, which to his surprise was accepted. The longer he worked on it, the more enthusiastic he became, until “Aida” eventually became, along with “Otello,” perhaps his greatest work. Verdi had little time to compose the opera; October 1871 had been agreed as the delivery date. At the same time, authentic stage materials and costumes were produced under Mariette’s supervision. But the Franco-German war put a spanner in the works, as the set produced in Paris was blocked and the performance had to be postponed for a year.

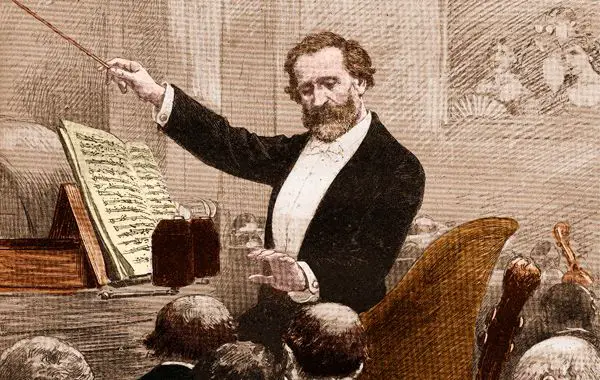

Verdi conducts Aida:

Verdi surprises the music world twice with 2 works of old age at the age of 74 (“Othello”) and 80 (“Falstaff”) years. The premieres become triumphs at La Scala. For Verdi, the two works signify the perfection of music drama: the unique position of Otello in the work of the great Italian master is linked to his consistent move towards the music drama of a through-composed opera. A path he had already embarked on with Macbeth and Simon Boccanegra and consistently continued with Otello. It is no longer the individual numbers that form the structure of the opera, but the dramatic units of the scenes. The flow of the plot and the music is no longer disturbed by the artificial division into recitative and aria. In addition, Arrigo Boito’s text is no longer structured in classical verse measures, but the verses are more natural and varied. As a result, the music gains in drama, to the detriment of the recurring melody. Of course, this is related to Wagner’s music drama and the infinite melody, even if Verdi, as a conscious Italian artist, rejected this several times.

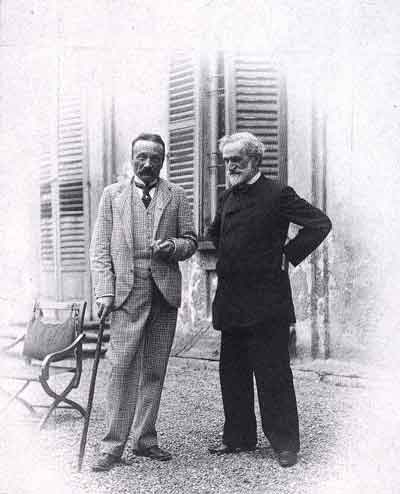

Verdi and Boito:

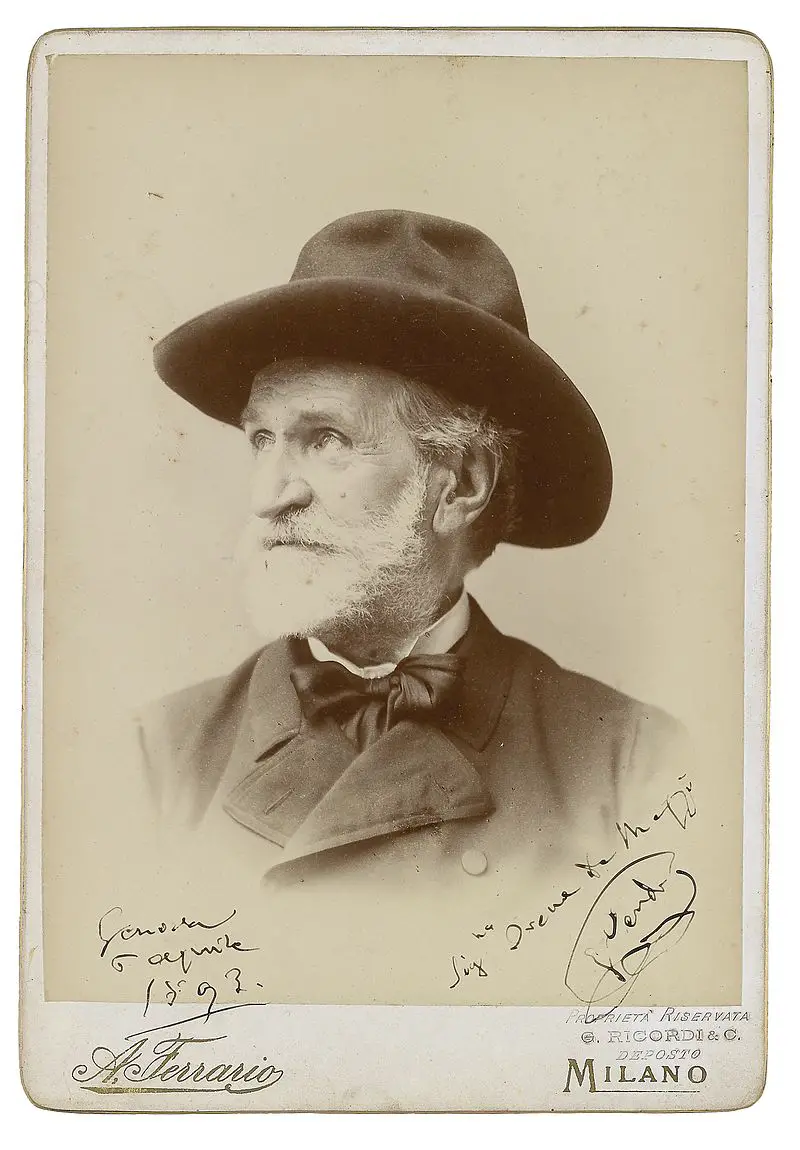

Verdi 1893:

FINAL RESTING PLACE IN THE CASA DI RIPOSO

In the last years of his life, Verdi initiated a generous deed. He bought a large area at the Piazza Buonarroti and had a rest home built there for impoverished, old musicians. He deliberately did not want to build a hospital-like nursing home, but a home for guests who were to live in 2-person rooms instead of dormitories. Since then, more than a thousand people have enjoyed this tastefully furnished boarding house, which, at Verdi’s request, was opened only after his death. He supervised the work meticulously and spoke “of his most beautiful work” (‘mia piu bella opera’). The garden with the crypt of Verdi and his wife Giuseppina is accessible by appointment at the reception, more (concert hall, Turkish room and many interesting memorabilia) depends on the events of the day.

After his wife Giuseppina died in 1897, Verdi often spent his remaining time in his suite at the Albergo Milano (now the Gran Hotel), where he died in his room in 1901.

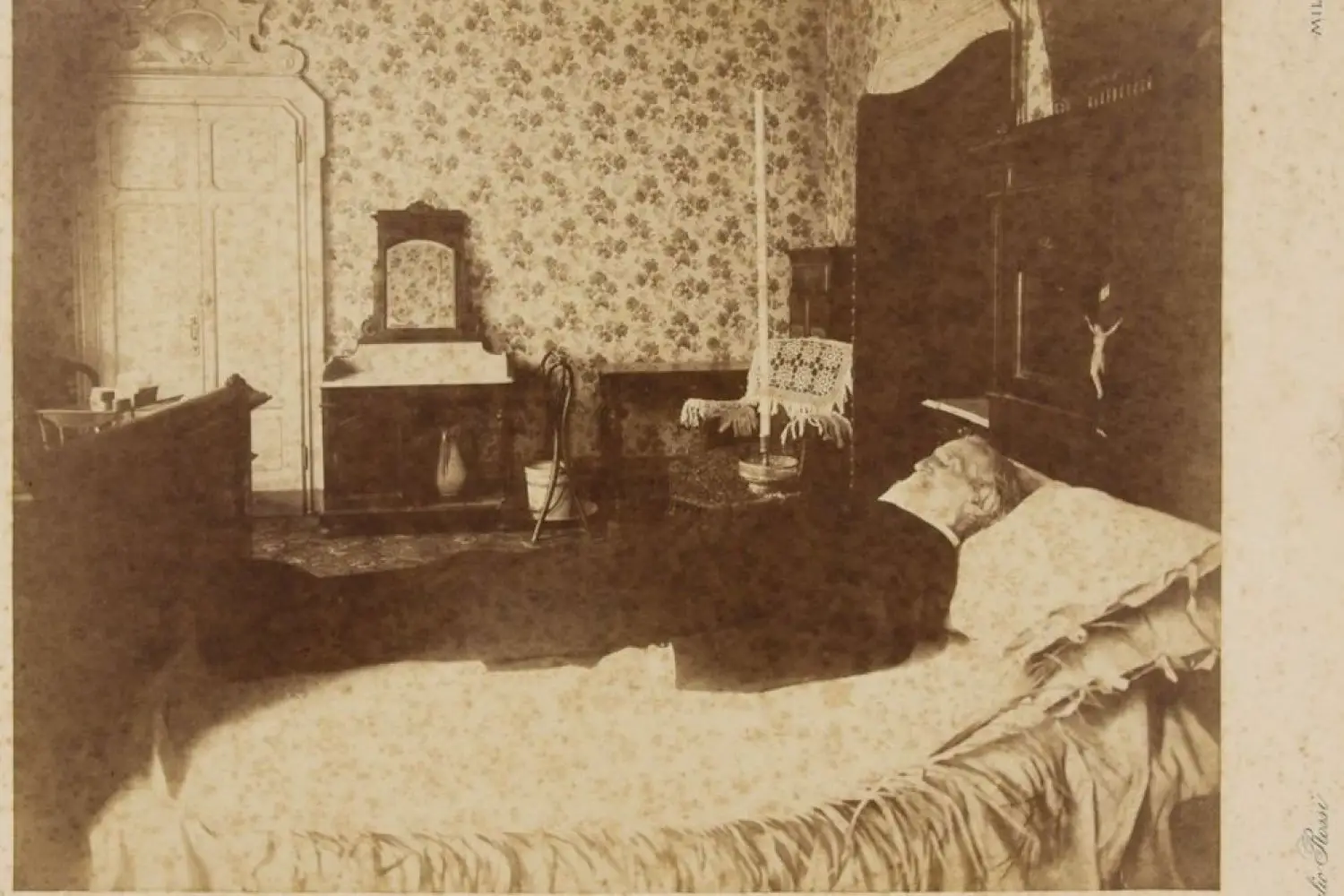

Verdi on his deathbed:

Modestly, according to his wishes, his body was taken to the cemetery for burial in a III class carriage. It was not until three weeks later that his body was transferred to the crypt of the Casa di riposo with the enormous participation of the Milanese population, accompanied by the singing of the estimated 300,000 people along the route who spontaneously sang “Va pensiero”. His death suite at the Gran Hotel has been preserved to this day and can be booked.

Casa di riposo (Casa Verdi) & Verdi’s tomb

The garden with the crypt of Verdi and his wife Giuseppina is accessible by appointment at the reception, more (concert hall, Turkish room and many interesting memorabilia) depends on the events of the day.

Casaverdi:

AIDA by Verdi – operaguide and synopsis | ♪ Opera guide (opera-inside.com)

DON CARLO by Verdi – the opera guide and synopsis | ♪ Opera guide (opera-inside.com)

MACBETH by Giuseppe Verdi – the opera guide and synopsis | ♪ Opera guide (opera-inside.com)

NABUCCO by Giuseppe Verdi – opera guide and synopsis | ♪ Opera guide (opera-inside.com)

OTELLO by Giuseppe Verdi – the opera guide and synopsis | ♪ Opera guide (opera-inside.com)

RIGOLETTO by Giuseppe Verdi – the opera guide | ♪ Opera guide (opera-inside.com)

SIMON BOCCANEGRA by Giuseppe Verdi – the opera guide and synopsis | ♪ Opera guide (opera-inside.com)

LA TRAVIATA by Giuseppe Verdi – opera guide & synopsis | ♪ Opera guide (opera-inside.com)

IL TROVATORE by Verdi – opera guide | ♪ Opera guide (opera-inside.com)

UN BALLO IN MASCHERA by Verdi – opera guide & synopsis | ♪ Opera guide (opera-inside.com)

Giuseppe Verdi Factsheet

Where was Verdi born?

Le Roncole

What was the name of his wife?

The first wife, who died at an early age, was Margherita Barezzi, the second wife was Giuseppina Strepponi.

In which places did Verdi live?

Le Roncole, Busseto, Milan, Sant’Agata (near Busseto), Paris

What were his most important works?

His many operas (among them Nabucco, Macbeth, Il Trovatore, La Traviata, Rigoletto, Don Carlo, Aida, Otello, Falstaff) and his Requiem

Where did Verdi die?

Mailand at Gran Hotel Milano

Where is his grave?

In Casa Verdi, Milan

How old did Verdi become?

87 Years

What was the cause of Verdi's death?

Brain hemorrhage

What was the date of Verdi's death?

January 21st 1901

Which was Verdi's most important rival?

Verdi himself produced no rivalries. His music was often compared with that of Richard Wagner. He was accused of copying the latter's musical drama, which annoyed Verdi greatly in each case.

With which artists did Verdi get along particularly well?

Verdi was a difficult man and lived a rather secluded life when he worked. Arrigo Boito, the librettist and musician was a close working partner in the late years. He knew Puccini, but was rather ambivalent about him.

Who were Verdi's most important librettists?

Solera mit 4 Libretti (among them Nabucco), Francesco Maria Piave with 8 Libretti (among them Ernani, Macbeth, La traviata, Rigoletto), Salavatore Cammarano with 4 Libretti (among them Il trovatore and Luisa Miller), Andrea Ghislanzoni with 2 Libretti (Aida and La forza del destino) and Arrigo Boito with 3 Libretti (among them Simon Boccanegra-Revision, Otello, Falstaff)

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!