PARSIFAL by Richard Wagner – the opera guide and synopsis

Online opera guide & synopsis to Wagner’s PARSIFAL

Like Verdi’s Falstaff and Puccini’s Turandot, “Parsifal” belongs to the last, age-wise words of a master. With “Parsifal”, Wagner was striving for something universal that would elevate the practice of art to the rank of a festival, a “stage-festival consecration play”, in Wagner’s words. This turned into a unique work that still captivates the listener with its mythical-religious theme and its spiritual and musical content.

Content

♪ Act I

♪ Act II

♪ Act III

♪ Act IV

Highlights

♪ Vorspiel

♪ Titurel, der fromme Held, der kannt’ ihn wohl

♪ Nun achte wohl und lass mich sehn

♪ Wie dünkt mich doch die Aue heute schön (Karfreitagszauber)

Recording recommendation

PREMIERE

Bayreuth, 1882

LIBRETTO

Richard Wagner based on Wolfram von Eschenbach's Tannhäuser tale, the chronicle of Arthurian legends by Chrétien de Troyes and various medieval sources.

THE MAIN ROLES

Amfortas, King of the Grail (baritone) - Gurnemanz, Knight of the Grail (bass) - Parsifal, ignorant fool (tenor) - Klingsor, renegade knight (bass) - Kundry, sorceress (soprano or mezzo-soprano) - Titurel, Amfortas' father (bass)

RECORDING RECOMMENDATION

PHILIPPS, Jess Thomas, Hans Hotter, George London, Martti Talvela, Gustav Neidlinger, Irene Dalis, conducted by Hans Knappertsbusch and the Chorus and Orchestra of the Bayreuth Festival.

THE SYNOPSIS

COMMENTARY

Biographical aspects

Wagner composed Parsifal in the last phase of his life (1878-1882) and he was aware that it would be his last work. He had been suffering from serious heart problems for many years. The attacks increased and he was permanently in a fragile health condition. In addition, his financial problems weighed heavily on him; the financial burden of the Festspielhaus, built in 1876, was enormous and, out of concern for his life’s work, had imposed a heavy workload on him in the seventies. The winters in Bayreuth were very cold and foggy and he escaped them by regular trips to the south, where he occasionally found inspiration for the composition of “Parsifal”. The visit to Rapallo in the garden of Palazzo Rufolo inspired him to Klingsor’s garden (“I have found the magic garden of Klingsor!”) and the cathedral in Siena became the model for the dome of Montsalvat.

Travel tip for opera lovers: Visit Villa Rufolo in Amalfi coast (Click for link to TRAVEL-blogpost)

Creation of the libretto

According to Wagner’s information, the first official draft of a plot sketch dated back to 1857; Wagner had even come across the Parzifal legend 10 years earlier during the famous Marienbad summer while preparing for “Tannhäuser”. The sketch from 1857 was lost; the definitive version was written down 20 years later. The entire prose text originated with Wagner, based on various Central European sagas. The most most important were Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Tannhäuser Tale and the Chronicle of the Arthurian Legends of Chrétien de Troyes.

When Wagner conceived the Grail saga, he had to make some decisions about its content, because some elements of the Arthurian saga are unclear regarding origin and design. For example, whether the Grail was a vessel or a stone or where the Montsalvat castle was located and named was unclear. In addition, he added his own ideas, the most significant of which is his own creation of Kundry, which was probably a result of Buddhist reincarnation mysticism (based on a legendary figure of “Cundrie la Surziere”).

The music

Wagner wanted to create a new orchestral sound for Bayreuth and Parsifal. He made it less brass-heavy than in the Ring and the timbres of the instruments flowed more into each other, which inspired Debussy. He was an ardent Wagner supporter and declared that “Pelléas” would have been unthinkable without “Parsifal”. The orchestral language became altogether more important in “Parsifal” and took up more space than in the previous works at the expense of the singing voice; the role of Parsifal is the shortest of all Wagner’s leading roles.

Wagner used leitmotifs in this work as usual. Their meaning had changed since the Ring. The connections between the motifs became even more important: they indicate affiliations (for example, diatonic motifs point to the Montsalvat world and chromatic motifs to Klingsor’s world), show connections (many small leitmotifs were derived from larger leitmotifs – so-called basic themes – see the example in the commentary on the overture), and there are groups of motifs that are musically related to each other (for example, Kundry’s motifs, the religious motifs, etc.). The motif architecture is very sophisticated and you will get to know about a dozen motifs in this opera portrait.

Interpretation

The interpretation of this work is not easy and is highly complex. As always, Wagner was careful not to leave an official interpretation of the work. He did, however, give quite a few interpretative hints, such as that the search for redemption and regeneration form the core theme, and he described the work as a stage festival, as something sacred-religious. Whether the statement is only Christian or more universal, mythical in nature is debatable. Although the relics and rituals used in this work are mainly of Christian origin, a reduction to Christian thought is not inevitable. Wagner wrote in his late years during and after the composition of Parsifal in his Bayreuth sheets some essays which even put the subject matter into the Aryan, anti-Semitic corner, but one should be aware that the (ideational) genesis of “Parsifal” goes back at least to the fifties and there Schopenhauerian worlds of thought dominated and certain approaches of the (aborted) Buddhist-inspired project “Die Sieger” served as a philosophical framework for “Parsifal”.

There is strangely little of Christian charity in this opera, all the more everything revolves around redemption, Wagner’s life theme. Almost all the characters who populate “Parsifal” want to be redeemed in some way. Amfortas from his physical pain, Kundry from her mental anguish, Gurnemanz and the knights from the involuntary abandonment of the ritual, and even Parsifal is redeemed by Kundry’s kiss. Wagner even spoke of the “redemption of the Redeemer” in the case of the latter.

Another important dimension of interpretation can be found in the veneareal desire. Superficially, we find symbols of the female in the Grail bowl and of the male in the spear. The knights can experience the life-giving of the Grail ritual only with united spear and bowl, although chastity is imposed on them. Amfortas became unchaste with Kundry and had to atone for it. Klingsor wanted to escape this severe test and emasculated himself. Such chastity, however, was inappropriate, since it had to come as “renunciation” from within. Consequently, Klngsor was cast out and became an avenger. This Schopenhauerian renunciation, which we already experienced in Hans Sachs, particularly resonated with Ludwig II, who may have experienced a sounding board through his own homosexuality. A unique figure is Kundry, who moves in both worlds. As late as Tannhäuser, Wagner neatly separated the whore (Venus) from the saint (Eve). In Parsifal, Kundry is the opaque servant in Montsalvat and “whore” in Klingsor’s realm, and becomes a schizophrenic woman, always in search of redemption through a pure one who can resist her luring arts and trigger tears and pity in her.

First performance and recension

Wagner had explicitly stated that “Parsifal” should only be performed in Bayreuth. Artistically, this was supported by the fact that he had geared the orchestration to the Festspielhaus and had conceived the work as a stage consecration festival, whose religious theme suited a “place of pilgrimage” such as Bayreuth, but would have been conceivably ill-suited to a “pleasure-seeking” theater. Moreover, the income from a Bayreuth-exclusive “Parsifal” was to help secure Bayreuth’s financial future. The premiere took place in Bayreuth in 1882 before an illustrious audience under the direction of Hermann Levi. The festival was held that year for the first time since the financial fiasco of 1876 and was devoted exclusively to “Parsifal.” In the sixteenth and final performance, Wagner took to baton for the third act, conducting for the last time in his life. Like Tristan, “Parsifal” produced a tremendous effect on fellow composers, among the most ardent admirers being Claude Debussy, Gustav Mahler and Giacomo Puccini. Legal protection of the work lasted 30 years, and from 1913 other theaters were allowed to perform the work (effectively there had been a handful of performances before then). The Metropolitan Opera even suggested that theaters should forego performances, but from 1913 a Parsifal mania gripped the world, with everyone wanting to present the work to their audiences. Wagner’s widow Cosima tried to extend the period of protection in the German Reichstag, but the motion was defeated.

Wieland Wagner’s 1951 Parsifal

After the Second World War, Bayreuth had to look for a new beginning. The first festival took place in 1951 and they sought this new beginning with a new production of Parsifal. Wagner’s grandson Wieland completely redesigned it. He renounced any naturalization and relied on a sparse stage set, supported by a haunting light direction. Even the dove appeared only as a point of light (which was to drive conductor Knappertsbusch up the wall). Musically, this new production was conducted by Hans Knappertsbusch, who maintained the tradition as a former assistant to Wagner associate and conductor Hans Richter with his broad tempos. This production was carefully assembled twice in terms of recording (1951 and 1962), and the ’62 version became the reference recording because of its better recording technique (stereo), even if the singers’ performance was slightly better in the ’51 recording.

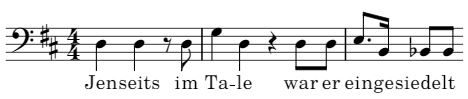

PARSIFAL PREHISTORY

Prehistory: Once King Titurel received from an angel the relics of Christ: the spear with which he was stabbed in the side on the cross of Golgahta and the chalice with which Christ’s blood was then captured. To protect these relics, he built the castle of Montsalvat on the northern, Christian side of the mountain and founded the Order of the Knights of the Grail, which only men who remain chaste out of inner conviction can join. Klingsor, a renegade knight, built himself a magic castle on the southern, Arabian side and sought to seduce the knights with his flower girls and steal the Grail. Titurel’s son Amfortas set out to defeat Klingsor with the help of the spear, which can defeat even holy knights. In Klingor’s magic garden, the chaste Amfortas was seduced by the demonic Kundry and Klingsor, was able to stal the spera in a moment of carelessness. He kept it and struck Amfortas a wound that never should heal.

PARSIFAL ACT I

The programmatic prelude

Synopsis: In a forest in the mountains of northern Spain. Not far from the Grail icastle Montsalvat.

Right at the beginning, the “love feast motif” is heard, an expansive theme:

The syncopated form is particularly striking; there is no sense of meter and a feeling of rapture, of floating. Wagner himself called it the central musical theme of this work. It will become the musical motif of the communion ritual of the finale of Act 1. Wagner created with this long theme a (in Wagner’s words) “basic theme,” in the sense that it can be broken down into three parts, each of which becomes a new motif again! We find the first part in the Grail motif, the second (minor) part becomes the pain motif and the third part becomes the spear motif.

After 3 times appearance of the love feast motive, we hear the so-called Grail motive, another central leitmotif of this work:

Right after that we hear the third important motif of the prelude. It is the short but powerful motif of faith:

In the first part of the prelude, we entered the musical world of Montsalvat, whose music was largely diatonic. With the sounding of a tremolo, the music becomes more chromatic and is dedicated to the thematic complex of suffering.

Vorspiel – Knappertsbusch

Amfortas vainly seeks release from his suffering

Synopsis: The Grail knight Goornemanz is at the forest lake not far from the castle. He is waiting with his squires at the edge of a forest lake for the king, who bathes in the cool lake every morning to let him forget his great pains for a moment. With him is Koondry, who has brought healing herbs from Arabia. Amfortas is carried here on a bed and gratefully accepts Koondry’s herbs. If they do not heal the king, she too is at her wits’ end. The king is carried to the lake.

For Wagner, Amfortas’ role was central. He compared his suffering “with that of the sick Tristan of the third act with an increase” (letter to Mathilde Wesendonck). Everything in this work revolves around his redemption by Parsifal. When he arrives, we hear his motif:

The prospect of cooling offf, the pain relief and the radiant nature of Montsalvat defies the suffering Amfortas with a beautiful theme, the so-called morning splendor motif:

At this point, something biographical/anecdotal should be interspersed. As with many of his works, Wagner had a muse for “Parsifal.” Cosima looked the other way when Wagner had an affair with his French admirer Judith Gautier during the 1876 Festival. Subsequently, when she returned to Paris, she became an important source of scents to send from Paris. Wagner was addicted to these essences and, for example, poured half a jug of iris milk into his daily bath. He called her “his Cundrie” who handed him essences, just as Kundry did with the suffering Amfortas.

Recht so! Habt Dank – van Dam / Hölle

Gurnemanz’ great narrative

Synopsis: The squires ask who the mysterious woman is. Goornemanz answers that she is a cursed woman who is expiating a debt. Half-dead, she was found in the forest at the time when the terrible thing happened to Amfortas. He tells the squires the story of Amforta’s wound, which has tormented him for years and has not closed since. The spear lies unreachable at Klingsor. In prayer, a voice had appeared to Amfortas, prophesying that only a pure fool, knowing through pity, could succeed in recovering the spear, heal the wound and redeem the king from his pains.

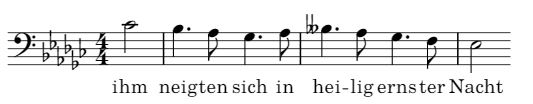

The great narrative of Gurnemanz reveals to us three further central musical motifs. When Gurnemanz tells deeply stirred the story of how Titurel once received the chalice and spear, the angelic motif is heard, which is related to the faith motif:

When Gurnemanz comes to talk about Klingsor, the mood changes and the Klingsor motif is heard:

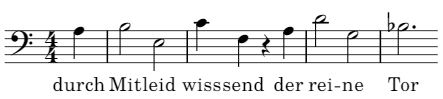

In the telling of the prophecy, when angelic voices spoke to Amfortas, we hear the Fool motif that we had already heard in the appearance of Amfortas:

It is a motif that is not magnificent, but offers a strange shadowing and is related to the Amfortas motif, as the foll shall provide Amfortas with the longed-for redemption by recapturing the spear.

In this scene we hear Kurt Moll, who was one of the great Gurnemanz. His voice is expressive and warm. We hear him in the Karajan recording.

Titurel, der fromme Held, der kannt’ ihn wohl

Parsifal appears and becomes a bearer of hope

Synopsis: Now a man appears with a dead swan in his hand, which he had shot from the sky with his bow. Goornemanz admonishes him that hunting is forbidden here.

This stranger is Parsifal, who appears with the motif named after him:

Because Parsifal is still a fool in this scene, his motif sounds inconspicuously; only in its radiant form will it resound jubilantly in the horns in the third movement.

Weh, Weh! Wer ist der Frevler – Hoffmann / Moll

The famous transition music

Synopsis: The Grail Knight demands to know the name of the hunter. Parsifal declares that he does not know it. Kundry explains that he was raised as a fool by his mother Herzeleide. Gurnemanz then invites the young man to the castle, hoping to have encountered the fool who will once steal the spear from Klingsor.

As Gurnemanz and Parsifal make their way to the castle, the magnificent transformation music is heard, introduced by the bell motif:

Verwandlungsmusik – Karajan

Wagner’s Grail Bells

As Gurnemanz and Parsifal approach the castle, they hear the bells. Wagner wanted a special bell sound, “two octaves lower than the bells of St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna”. But this would have required four bells of 280 tons of steel for the four notes. Wagner had the Bayreuth piano manufacturer build an unusual instrument that produced the peculiar sound Wagner wanted. In the twenties, Siegfried Wagner and the conductor Karl Muck rethought and the result of the instrument makers looked like giant wine barrels with strings stretched over them. Unfortunately, they were melted down during the war years. They can still be heard in a recording by Muck from the twenties and seen in a photograph.

The great communion ritual begins

Synopsis: In the hall of Montsalvat, Parsifal witnesses the communion ritual to which Gurnemanz invites him in order to win Parsifal over to their cause. Solemnly the knights march up. Finally, Amfortas is carried in.

This entry is accompanied by long, overwhelming music. The choral music is sung by visible, moving choral groups, as well as by invisible choral groups resounding from above. This scene is again driven by the bell motif, whose striding, dotted motif suggests the entry of the knights. In the first part, we hear the knights’ chorus creating an immediate effect with strong crescendi and decrescendi. With the “Chorus from the middle heights,” a change of mood occurs in the second part (Den sündigen Welten). With the “Boys’ Choir from the extreme Heights of the Dome,” the music changes to the ethereal in the third part.

Nun achte wohl und lass mich sehn – Levine

Amforta’s moving monologue

Synopsis: The voice of Amfortas’ father is heard, exhorting his son to do his duty and begin the life-sustaining ceremony. But Amfortas, tormented by his pain, which is intensified by the ritual, wants to refuse the ritual and longs for his death.

Nein, lasst ihn unenthüllt – Weikl

The unveiling of the Grail

Synopsis: The bowl is solemnly unveiled, a ray of light penetrates from above and it shines in luminous purple. Amfortas blesses bread and wine, all are on their knees.

Once again, a great choral scene resounds with the unveiling of the Grail.

Enthüllet den Gral – Karajan

Synopsis: The knights take the Lord’s supper. Amfortas then leaves the hall, followed by the knights. Gurnemanz and Parsifal remain behind. Questioning, the knight turns to the fool, but Parsifal remains unimpressed and Gurnemanz throws him out of the hall with the words “You are just a fool. A voice sounds from above: «Enlightened through compassion, the innocent fool»

Wein und Brot des letzten Mahles – Karajan

PARSIFAL ACT II

Klingsor instructs Kundry to seduce Parsifal

Synopsis: In Klingsor’s magic castle. Kundry has returned to Klingsor, he was able to lure her to him again. Parsifal approaches the castle on his way from Montsalvat and Klingsor orders Kundry to seduce Parsifal as she once did with Amfortas.

Die Zeit ist da

Synopsis: Parsifal appears in Klingsor’s garden. There, the flower girls try to seduce Parsifal, but without success.

Wagner himself called the music of the ghostly flower girls “scent music,” and designed it with its own musical motifs

Scene of the flowergirls – Jordan

Synopsis: Kundry enters this scene in transformed form as a young woman. She calls him Parsifal, thus revealing his true name. She tells him about his mother, who wanted to protect him but died in his absence out of worry.

Wagner wrote this scene, in which Kundry tries to exploit Parsifal’s feelings for his mother, in the style of a lullaby.

We hear this passage in two interpretations.

Christa Ludwig was an excellent Kundry. She was already a brilliant seductress as Venus, Kundry’s alter ego.

Ich sah das Kind – Ludwig

In 1950 Maria Callas sang Kundry, it was the the last time she appeared in a Wagnerian role. It took place in Rome, sung in Italian. The effect is amazing. It is not only Callas’ voice that sounds “different,” but also the Italian language, with its flowing, softer vowels and consonants, gives the scene a dreamy note.

Ich sah das Kind – Callas

Kundry’s seduction attempt

Synopsis: Self-reproach and pity for his mother seize Parsifal. Kundry tries to exploit his grief. But the kiss on his mouth, which she disguises as a last greeting from his mother, has the opposite effect. Through her embrace he now feels pity. He recognizes Amforta’s pain and pushes Kundry away.

Parsifal’s outburst at “Amfortas! Die Wunde” is the great turning point of this opera. Here he transforms from the pure fool to the knowing compassionate one.

We hear Jonas Kaufmann in this passage, he sings Parsifal with a powerful voice and Kundry trudges in the ankle-deep blood of the Metropolitan production from the Wagner year 2013.

Amfortas! – Die Wunde! – Kaufmann

Synopsis: Kundry does not give up. She wants him to feel pity for her and redeem her, who once laughed mockingly in the face of the Savior on the cross. But Parsifal now knows his mission.

For Kundry, too, this scene is the great turning point; with this confession her atonement begins.

We hear Martha Mödl, one of the great voice dramatists and the Kundry of the fifties. She was the exclusive Kundry of Bayreuth for almost two decades.

Grausamer! Fühlst im Herz nur and’rer Schmerzen – Mödl

Klingsor appears and tries to turn the tide

Synopsis: Kundry sees the unsuccessfulness of her efforts and calls Klingsor to her aid. He appears with the spear and hurls it at Parsifal’s head, but Parsifal seizes the flying spear and holds it above his head, banishing Klingsor’s spell by drawing a cross with the spear. The castle sinks and the garden withers to a wasteland. Parsifal looks at the slumped Kundry and calls out to her that she knows where to find him. He sets off in search of Montsalvat.

Vergeh, unseliges Weib – Hofmann / Vejzovic / Nimsgern

PARSIFAL ACT III

The wasteland of Montsalvat

Synopsis: In the area of Montsalvat, it’s spring.

The prelude to the second act opens with a bleak motif. This desolate mood describes the decline of the knights’ league. The overture is played only by strings in the style of a string quartet. The music is chromatic, remains in piano and is immediately reminiscent of the third act of “Tristan”.

Vorspiel – Petrenko

The return of Parsifal

Synopsis: Gurnemanz hears a groan. He discovers Kundry lying half frozen on the floor in her penitential robe. When he wakes her up, she appears transformed. Then they discover a knight in the distance, who carries a spear in his hand. When he takes off his helmet, they recognize the fool who had visited them many years ago. Gurnemanz tells him about the decline of the knighthood, the death of Titurel, who had to die without the life-giving effect of the ritual, and that Amfortas has been refusing the Grail ritual for years in order to force his death. Parsifal, for his part, tells him of his years-long, rocky journey in search of Montsalvat, where he wanted to return the spear.

Moved, accompanied by the angelic motif, Gurnemanz recognizes the return of the spear and tells of the fate of the brotherhood.

O Herr! War es ein Fluch, der dich vom rechten Pfad vertrieb – Weber / Vinay

The blessing of Parsifal

Synopsis: Parsifal collapses exhausted. Gurnemanz, knowing that he has Amfortas’ successor before him, blesses Parsifal while Kundry washes his feet. He then anoints Parsifal’s head and welcomes him as Amfortas’ successor.

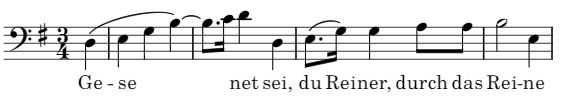

With the words of Gurnemanz “Gesegnet sei, du Reiner, durch das Reine” (May this purity bless you, pure one!), the magnificent blessing motif resounds:

Accompanied by pathetic brass, Gurnemanz then performs the unction:

Gesegnet sei, du Reiner – Sotin / Hoffmann

The Good Friday spell

Synopsis: Parsifal, for his part, turns to Kundry and performs the baptism to redeem her from her torment and guilt. Parsifal recognizes the beauty of nature and life again for a long time.

Wagner called this famous scene, which takes place after Kundry’s baptism, “Good Friday spell,” which, like the Waldweben, is an orchestral interlude inspired by Beethoven’s Pastorale. It is characterized by the so-called flower meadow motif, which is played by the oboe and describes the graceful colors, shapes and scents of the forest and meadow:

Wie dünkt mich doch die Aue heute schön – Thomas / Hotter

Synopsis: Now the three go to the castle. Parsifal carries the spear solemnly before him.

With the transformation music, we hear the bell music again (see Act I), but another melancholic motif still weighs in the basses.

Mittag. Die Stund ist da – Moll

The Good Friday Ritual

Synopsis: It is Good Friday and in the great hall of Montsalvat the knights meet for the ritual. The coffined body of Titurel and the litter are brought in.

Geleiten wir im bergenden Schrein – Karajan

The healing

Synopsis: Amfortas stands in front of the shrine. Painfully, Amfortas feels the guilt of his father’s death because he never revealed the Grail again. The knights implore him to reveal the life-giving Grail. Amfortas asks them to kill him to redeem him and presents them with the wound. Parsifal enters this scene and touches the open wound with the spearhead, which miraculously closes. He presents the spear to the knighthood and himself as the new king.

Nur eine Waffe taugt die Wunde schließt – Kaufmann

Synopsis: Parsifal now performs the ritual as the new Grail King and the Grail glows again. A white dove descends from the dome and hovers over Parsifal’s head.

Once again the heavenly choir resounds from the dome of the church.

Höchsten Heiles Wunder! – Knappertsbusch

Peter Lutz, opera-inside, the online opera guide to PARSIFAL by Richard Wagner

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!