DIE MEISTERSINGER VON NÜRNBERG by Richard Wagner – the opera guide and synopsis

Online opera guide & synopsis to Wagner’s DIE MEISTERSINGER VON NÜRNBERG

The Meistersinger are perhaps Wagner’s greatest stroke of genius. The musical themes are dazzling, the orchestration and compositional technique is masterful, the plot is originally designed, and with Hans Sachs, Wagner has created a unique role-portrait.

Content

♪ Act I

♪ Act II

♪ Act III

Highlights

♪ Vorspiel Ouverture

♪ Da zu Dir der Heiland kam When the saviour came to thee

♪ Was duftet doch der Flieder Flieder monologue

♪ Nun eilt herbei … Frohsinn und Laune

♪ Wahn! Wahn! Wahn monologue

♪ O Sachs! Mein Freund! Du treuer Mann!

♪ Selig wie die Sonne Quintet

♪ Silentium Entrance of the Mastersingers

♪ Wachet auf! Es nahet gen den Tag

♪ Morgen ich leuchte im rosigem Schein Beckmesser’s prize song

♪ Morgenlich leuchtend im rosigen Schein Walther’s prize song

♪ Verachtet mir die Meister nicht … Ehrt Eure deutschen Meister

Recording recommendation

PREMIERE

Munich, 1868

LIBRETTO

Richard Wagner, inspired by Deinhardstein's comedy Hans Sachs

THE MAIN ROLES

Hans Sachs, Meistersinger and cobbler (baritone) - Veit Pogner, Meistersinger and goldsmith (bass) - Sixtus Beckmesser, Meistersinger and town clerk (baritone) - Walther von Stolzing, young knight from Franconia (tenor) - David, Hans Sachs' apprentice (tenor) - Eva, Pogner's daughter (soprano) - Magdalena, Eva's guardian and David's friend (mezzo-soprano)

RECORDING RECOMMENDATION

CALIG, Thomas Stewart, Sandor Konya, Gundula Janowitz, Thomas Hemsley, Brigitte Fassbaender conducted by Rafael Kubelik and the Bavarian Radio Choir and Orchestra.

COMMENTARY

The historical background extends over 32 years

As a 15-year-old Wagner saw Deinhardstein’s comedy “Hans Sachs” on a Dresden stage, which captivated him instantly. It was about the Nuremberg poet and Meistersinger Sachs, who was known for his poetry in the 16th century. The art of the Mastersingers went back to minstrels who made music according to free rules and who recorded their art rules in fixed tablatures as they gradually settled in the cities. This art was subsequently administered by the guild masters, of whom the shoemaker Sachs was the most famous.

17 years after his experience in the Dresden theatre, Wagner felt the need to create a cheerful counterpart to the tragic “Tannhäuser”. He recollected the comedy and created his first sketches in 1845 during a spa stay in Marienbad. His involvement in the Dresden Revolution and the hectic flight to Switzerland interrupted the work and it was to take another 15 years before he resumed work.

There were two reasons for this. The first occasion was his relationship with Mathilde Wesendonck, which we will discuss in the next section. Wagner also came across a chronicle by Wagenseil (“von den Meisters Singer holdseligen Kunst”), which gave him a comprehensive insight into the rules and regulations of the Meistersinger.

Secondly, in 1861, he was once again troubled by financial worries. In order to make money quickly, he created a draft text of the Meistersinger and promised his publisher Schott speedy work and the delivery of an opera within a year. Schott paid a hefty advance, and Wagner moved to Biebrich near Mainz to take up work in peace and quiet and be near his new flame, Mathilde Maier. After the first successful beginnings, his creative power began to falter, and Wagner felt unable to finish the opera. Coldheartedly he sent his publisher the (already mortgaged) manuscripts of the Wesendonck-Lieder instead of the opera, but the publisher refused to inject further funds into the project.

It was not until three years later that the work on the opera continued. Ludwig II of Bavaria relieved him of his financial needs and he was able to complete the work by 1867.

Mathilde Wesendonck and Schopenhauer: Love as Delusion

At the invitation of his Zurich patrons, the Wesendonck couple, Wagner spent a few days with them in Venice in 1861. There he discovered that his secret lover Mathilde Wesendonck was pregnant with her husband’s fifth child. After the love affair was already in a crisis, Wagner realized that this love, which inspired him to “Tristan & Isolde” was over. Now Wagner decided to philosophically transcend this indirect “rejection” and saw himself as Hans Sachs, who renounced love for noble reasons.

The philosophical framework for this was provided by Schopenhauer’s work “Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung” (The World as Will and representation”), which he had become acquainted with a few years earlier. In Schopenhauer’s pessimistic view of the world, the will of the predator “man” results in destructive torments. This inherent mania leads to war, self-destruction and loss of love, whose only way out is renunciation (of the will).

Hans Sachs

Thus the shoemaker poet Hans Sachs became a Schopenhauer figure whose world philosophy Wagner expounded in the delusional monologue of the third act. This philosophical change explains the paramount importance of Hans Sachs’ figure in Wagner’s Meistersinger: Sachs is the master himself. Wagner identified himself with no other figure more than the cobbler-poet, and he has him quoted in the third act “Tristan and Isolde”: «Mein Kind, von Tristan und Isolde kenn’ ich ein traurig Stück. Hans Sachs war klug und wollte nichts von Herrn Markes Glück». (“My child, I know a sad tale of Tristan and Isolde. Hans Sachs was clever and did not want anything of King Marke’s lot”). Isolde now became Eva!

Apart from Sachs, all other figures fade away, even the revolutionary hero and iconoclast Walther (who also has a little Wagner in him) must take a back seat to the light figure Sachs. If the Junker Walther were the hero of the final act in a “normal” opera, the third act now becomes the two-hour “Hans Sachs Festival”, which begins with his Wahn-monologue and ends with his «Verachtet mir die Meister nicht» (“Don’t despise me the masters”), forming one of the most gigantic par force tours in all of opera literature.

The part of Sachs demands the whole range of the singer’s repertoire: high lyrical passages, long declamatory stretches and of course the high passages of the third act and the enormous final scene.

Sixtus Beckmesser

Wagner choose the name of the confirmed bachelor from document of Hans Sachs. Wagner freely invented everything else. Originally, he called the figure of Merker “Hans Lick” or “Veit Hanslich” and referred to the dreaded Viennese music critic Hanslick. The latter was fond of Wagner in his early years and was one of the first to write a benevolent review of the newly published Tannhäuser in 1845. He won the composer’s trust and in the same year saw first sketches of the Meistersinger. Later, he turned away from Wagner’s music and wrote bitterly angry words about Lohengrin (“miserable musical thought”) or Tristan (“the systemized non-music”).

Wagner maliciously invited the critic in 1862, when he read the complete poetry of the Meistersinger for the first time in a small circle. Hanslick understood the allusion (the character’s name was still Hans Lick there) and later, as spokesman for the “conservatives” around Brahms, became a powerful adversary against “the new Germans school” around Wagner.

In keeping with the Nibelung Mime from the ring, Beckmesser’s music is uninspired and unmusical, for the art critic’s person is not creative, but can only administer the past. This is the highest possible humiliation Wagner can pronounce and attributes (unspeakably) both figures with Jewish stereotypes. Wagner wrongly assumed that Hanslick had Jewish roots.

The Music

To what extent do the chronologically adjacent Meistersinger and Tristan differ! Following the inward chromatic tragedy of Tristan, Wagner wrote the bright, comic “C major chalybeate bathe” (Hans Richter) of the Meistersinger. Common to both works is the use of leitmotifs. Wagner uses about 30 leitmotifs in the Meistersinger, five of which we will discuss further below in the section of the overture. A special feature of the Meistersinger is the polyphonic structure of the composition. Wagner wanted to emphasize the historical component of the work and called the formal rigor and counterpoint “applied Bach”. Its crowning glory is perhaps the grandiose fugal scene of the quarrel scene.

“Honor your German masters”

The famous final scene with Sachs’ speech is one of the key scenes of this opera. The Nazis used the “Meistersinger” as a shop window, and Winifred Wagner compliantly accompanied the Reich Party Rallies in Nuremberg with glittering performances of the “Meistersinger” in nearby Bayreuth, for the first time in 1933.

It is difficult after the National Socialist years to interpret the end of this opera neutrally. Wagner saw the meistersinger as a highly political work and commented on his thoughts in the essay “Was ist deutsch”. Wagner planned to found a (Wagner-centered) national center to rejuvenate german art , which resisted being taken over by the superficiality of Italian and French art. To this end he proposed to Ludwig II to found an academy for German singers and musicians be founded in Nuremberg.

Wagner published the paper “was ist deutsch” in Munich daily newspapers. He had to accept severe reproaches for this from his patron Ludwig II, because the latter was about to lose his independence from Prussia and was vehemently fighting everything national German. When seeing the opera for the first time, he eyes were filled with tears and he seems to have overlooked Sachs’ final speech, or he was simply blind to reality.

As always, Wagner was also inconsistent in this plan. He presented this Meistersinger opera to the king and patron of the arts as a primary product of German artistrty, but it is obviously written in the form of a historicizing French Grand Opéra, whose epigone was the Jewish (ergo: not creative) Meyerbeer.

The premiere in Munich

The premiere took place on June 21, 1868, in Munich at the Royal National Theater in the presence of the king. It was highly acclaimed and Wagner received one of the greatest ovations of his life.

Wagner accepted the applause in the king’s box. In doing so, he violated court etiquette when he stepped forward and bowed, which was reserved only for the king. But the king stood blissfully two steps behind him and wrote a letter of homage to the master in the early hours of the morning.

DIE MEISTERSINGER VON NÜRNBERG ACT I

The radiant prelude

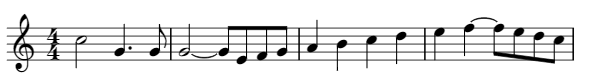

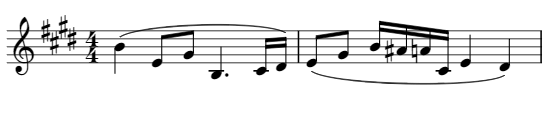

The magnificent prelude has become one of Wagner’s most famous concert pieces. Wagner introduces some of his wonderful leitmotifs and lets them shine polyphonically in the orchestral parts. We get to know five of the most important leitmotifs of the opera. At the beginning we hear the Meistersinger motif in radiant C major, which portrays the dignity and sublimity of the masters:

Next, Walther’s urgent love motif is heard, with the falling fourths (which will reappear in the Beckmesser caricature):

Shortly afterwards, the Meistersinger March appears, a fanfare-like theme that Wagner took from a historical Meistersinger songbook

And immediately after that we hear the guild motif:

After a longer transition we hear the tender and expressive Passion motif, which later becomes part of the price song.

Vorspiel

Synopsis: In the St. Catherine’s church in Nuremberg a church service is celebrated. During the congregation’s final hymn, Eva and Walter exchange longing looks.

In this church scene, Wagner quotes the Luther chorale “Eine feste Burg” (A Strong Castle), possibly a reminiscence of Wagner’s revolutionary years, for the chorale was not only “the hymn of the Reformation” but also a battle song of the revolutionaries of the July Revolution.

Da zu Dir der Heiland kam (When the saviour came to thee)

Walther learns the rules of tablature from David

Synopsis: Walther only came to Nuremberg the day before and fell head over heels in love with Eva the day before. He intercepts her when she goes out and wants to know if she is already engaged. Their conversation is interrupted by Eva’s companion, maid Magdalena, who tells him that a groom will soon be chosen at a singing competition of the mastersinger. Walther can just about arrange a rendezvous for the evening when Magdalena pulls Eva out of the church, with the remark that David could explain more about the competition to him. The apprentice boys enter the church. David, the oldest apprentice, explains to Walther the strict rules, which take years to learn. Only master singers who have passed the audition are allowed to take part in the competition. During the audition, the marker marks with chalk the mistakes in the work, whose text and music the candidates had to create from their own abilities. At the eighth stroke, the candidate fails the audition. Walther decides to audition for the Mastersingers and watches how the apprentices set up the church hall for the Mastersingers’ meeting.

So bleibt mir einzig der Meister Lohn! – Domingo / Laubenthal

Synopsis: The textbooks step reverently aside as Pogner and Beckmesser enter. The aging Beckmesser is the Marker and intends to enter the contest. When Walther turns to Pogner for an opportunity to audition, Beckmesser tries to convince Pogner to reject the rival’s application. Then the other Meistersingers enter, and the session begins with the somewhat long-winded opening by Kothner.

Sei meiner Treue wohl versehen – Weikl / Moll / Bailey / Kollo

Pogner announces the rules of the mastersinger contest

Synopsis: Pogner takes the floor. He announces the rules for the contest of the following day. The winner will have the right to marry his daughter Eva, but she has the right to reject him. Beckmesser interjects that this renders the verdict meaningless.

Wagner portrays Pogner musically and lyrically as a likeable but rather jovial person, who Sachs (Wagner) cannot hold a candle to, the depth of Sachs is missing.

Das schöne Fest Johannistag – Frick

Synopsis: Sachs suggests that the people should have the last word, but the masters are against it. Beckmesser wants to know if Sachs is also applying, whereupon the latter maliciously remarks that he and Beckmesser are probably already too old. Pogner now suggests that the Junker be heard, he vouches for him himself. Walther introduces himself with a song as a minnesinger who learned the singing of Walther of the bird pasture and the birds. His lecture is accompanied by the violent head shaking of the masters. Only Sachs defends him. Walther is admitted despite Beckmesser’s furious protest. Kothner reads out the rules of the song and Beckmesser goes to the Merkerstuhl. Walther takes a seat in the singer’s chair and begins singing a passionate minnesong about spring, accompanied by the scratching of the markers’ chalk.

Fanget an! – Domingo

Synopsis: After the first verse Beckmesser jumps out of the Merkerstuhl and interrupts the singer, saying that he has forfeited his right, since the chalkboard is already full of stroke. The other mastersingers agree with him; only Sachs stands defends Walther and accuses Beckmesser of wanting to eliminate a competitor. Beckmesser angrily replies that the cobbler should rather take care of the overdue shoes he had ordered for the competition. Sachs sends Beckmesser back to the Merkerstuhl and Walther begins the second verse. The scratching of the chalk begins again and soon the singing of Walther can hardly be heard any more because of all the commotion. Even the apprentices mock Walther and the masters decide that the singer has failed.

Wagner composed a masterly hullabaloo of master singers’ voices, concluded by the mocking performance of the Meistersinger motif by a bassoon.

Seid ihr nun fertig? – Jochum

DIE MEISTERSINGER VON NÜRNBERG ACT II

Synopsis: It is evening in the alleys of Nuremberg. In front of the Pogners’ house the apprentices are gathered. Magdalena learns from David that Walther had failed the test.

The short prelude “smells” wonderfully summery with its trills of the strings and winds and the triangle sounds. Afterwards a swinging choral song sounds on St. John’s Day, the feast on Midsummer’s day.

Johannistag – Solti

Synopsis: Eva and Pogner return home from a walk. Worried that she has not heard from Walther, Eva gropingly asks her father whether she really has to marry the winner. Her father replies that the choice is ultimately up to her. When she inquires about the knight, it dawns on Pogner that she might be in love with him.

Lasst sehen, ob der Meister zu Hause

Sachs’ Flieder monologue

Synopsis: Shortly after Eva and Pogner enter the house, their neighbor Sachs sits in front of his house to finish cobbling Beckmesser’s shoes. He pauses, enjoys the scent of the lilac and thinks back to the audition singing. Walther’s song sounded beguiling, but did not follow the rules, and yet Sachs found no fault.

There is peace at night. In the clarinet, the motif of Walther’s prize song can still be heard. The chirping of the violins and the solemnly muted winds create a beautiful atmosphere. As it becomes more moving, a busy rhythm can be heard in the orchestra, Wagner’s reference to historic Guild Songs. In the Middle Ages, all guilds had their own songs, the rhythm of which was taken from their work process.

After this (recitative-like) introduction, an ariose passage develops. The Lilac Monologue is basically a classical number piece, Wagner did not want to call it an aria, too much it would have sounded like a Welsh opera, so he called it a “monologue”.

The piece closes with the beautiful coda «dem Vogel, der heut sang, dem war der Schnabel hold gewachsen» («The bird that sang today, had a finely formed beak»).

Was duftet doch der Flieder – Finley

Eva proposes to Sachs

Synopsis: Eva joins Sachs. She knows that Beckmesser wants to win the competition and lets him know blatantly that she would not mind if Sachs, a widower, were to win the contest. But Sachs, although he has feelings for Eva, protests feeling too old to be her husband. He also knows that Eva is in love with the knight. When Eva talks about Walther, Sachs says that someone like Stolzing, who was born to be a master, has a difficult position among the masters. Eva wants to know if none of the masters can help him, and he advises her to forget him. Angry, Eva leaves the master shoemaker, who is now tormented by a guilty conscience.

For this duet, which oscillates so strangely between father-daughter relationship and coquettish flirtation, Wagner has written music with flowing lines and undulating rhythm. Again and again, wind instruments comment on Eva’s erotic allusions.

Gut’n Abend, Meister – Janowitz / Weikl

Synopsis: Magdalena meets the angry Eva and tells her that Beckmesser wants to serenade Eva. Eva asks her to disguise herself and pose as Eva at the window and hurries to the secret meeting with Walther, who is upset and depressed about the Mastersingers’ verdict.

Da ist er – Lorengar / King / Love

Walther and Eva plan the escape

Synopsis: Eva swears him love and the two decide to flee together. When they go into the house to pack the most necessary belongings, the night watchman appears, who uses his horn to admonish the citizens to be careful.

Geliebter spare Dir den Zorn!

Synopsis: Sachs was able to overhear the conversation and sees Eva and Walther ready to flee the house. Quickwitted, he illuminates with a lamp the alleyway through which the two wanted to flee unrecognized; now they must hide and become witnesses to the following scene. In the dark, they see Beckmesser approaching Eve’s balcony and his lute tuning. Sachs deliberately knocks on the shoes to disturb Beckmesser. Angered, Beckmesser demands that the cobbler stop knocking, but Sachs points out that he is just finishing Beckmesser’s shoes for the singing contest.

Jerum! Jerum . Bailey / Weikl

Beckmesser’s serenade

Synopsis: Now Sachs plays a nasty trick on the marker. Flatteringly, he says that he wants to learn the job of the marker from Beckmesser, and instead of drawing chalk lines, he’ll knock the nails into the shoe. Reluctantly, Beckmesser responds to this. Now Beckmesser can finally begin the serenade for the supposed Eve, but soon he hears the first blow on the shoe. The longer the song lasts, the more frequent the blows and the more Beckmesser gets out of control.

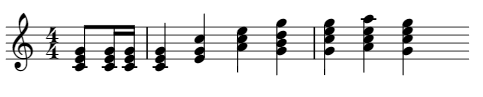

After tuning the lute you hear the Beckmesser motif:

Remarkable are the pitiful falling fourths, which only seem like a miserable caricature of the falling fourths of Walther’s radiant love motif (compare the leitmotif in the section on prelude).

Den Tag seh ich erscheinen – Weikl

The great quarrel scene

Synopsis: To drown out the knocking, Beckmesser sings louder and louder. The noise attracts onlookers. When David arrives, he sees Beckmesser serenading his beloved Margarethe and rushes to the marker. The whole city now participates in a wild brawl. When the night watchman’s horn sounds, women pour cold water from the windows onto the crowd and everyone takes refuge in their houses. Sachs quickly pushes Eve to her father and pulls David and Walther into his house.

The famous quarel scene has a biographical background: Wagner visited Munich with his brother-in-law at a young age and one evening he fooled a young man into believing he is looking for singers for a theatre. When the wanna-be singer started rehearsing in the street and realized that he was the victim of a swindle, a wild brawl ensued in which dozens of people took part.

Wagner turned this reminiscence into a gigantic work of art. This scene, composed in the form of a fugue, is musically complex. More than one hundred soloists and choristers, together with another one hundred people in the orchestra pit, perform a gigantic fugal jumble, which develops into a long and grand crescendo until the night watchman arrives and the scene ends magically quietly in the moonlight.

Prügelszene – Metropolitan Opera

DIE MEISTERSINGER VON NÜRNBERG ACT III

Synopsis: It is early in the morning. Sachs is sitting in his cobbler’s workshop, absorbed in the reading of a folio.

Vorspiel – Solti

Sachs‘ “Wahn monologue”

Synopsis: David enters the workshop and apologizes for his behavior in the night. Sachs does not respond, but kindly asks him to sing the verses for Saint John’s Day. After the song, Sachs asks him to dress festively at home and come back as his herald. When David is gone, he begins to brood. He makes the decision to help Eva and Walther.

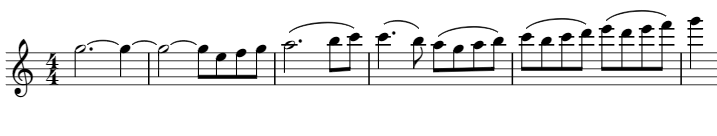

The monologue begins with Sachs’ renunciation motif in the strings:

The monologue is in three parts and begins with the resigned realization that man’s delusion drives things. Then a musical reminiscence of the beating scene is heard, and finally the love motif sounds with the decision of Saxony to steer the madness and bring the lovers together.

Wahn! Wahn! – Weikl

Synopsis: There Walther steps into his workshop. He tells the master that he had a beautiful dream at night. Sachs asks him to make a song out of it; he will help him to form a master song. Walther now sings the poem to him about how he met a beautiful woman as a wanderer in paradise. Sachs takes down the words. Touched by his skill, he instructs the young man until the second verse is completed. For Walther, the song is over. Sachs admonishes him to add the interpretation of dreams to a third verse, as the rules require. Only in this way can he hope to participate in the competition.

Morgendlich leuchtend im rosigem Schein – Domingo / Fischer-Dieskau

The great pantomime music

Synopsis: Sachs and Walther leave the room to get ready for the festival. Beckmesser steps into the workshop, he wants to visit Sachs to get his shoes. He is dressed up but in a suffering condition; David’s beating has left its mark. He is even more tormented by the fear that his prize song is not enough. Suddenly his gaze falls on Walther’s poem, which Sachs had co-written. He quickly packs it away. Sachs enters the workshop, and Beckmesser immediately accuses him of having deliberately disturbed his wooing for Eva the night before in order to get her himself. Sachs replies that he will not woo Eva. Triumphantly, Beckmesser waves the paper.

Wagner wrote a great soundtrack to Beckmesser’s appearance. It is a veritable musical pantomime that describes the beaten up, clumsy Beckmesser snooping around the workshop.

Ein Werbelied von Sachs – Solti

Synopsis: Sachs generously donates the song to Beckmesser, who now cheers, since to get a text by the poet Sachs is like winning the lottery. Suspiciously, Beckmesser scents a ruse, but Sachs promises him that he would never tell anyone that the text was written by him. He also admonishes him to study the text carefully, saying that the lecture is not easy. Overbearingly, Beckmesser reassures him that musically no one can hold a candle to Merker. Embracing Sachs, he leaves the workshop to learn the song by heart. Smiling, Sachs sits down in a chair, knowing that Beckmesser will be overwhelmed by the text. Now Sachs notices Eva, who has entered the workshop and is richely dressed. She claims that the new shoes pinch, but she actually came just to see if Walther is there. When Walther enters, Sachs deals with the shoe and leaves the two lovers alone. Happy, Sachs now hears Walther perform the third verse of the song for Eva.

Weilten die Sterne im lieblichen Tanz? – Domingo

Synopsis: Eva now understands everything. She bursts in a sudden fit of weeping and sinks on Sachs’ breast in gratitude. Walther steps up to them and wrings Sachs’ hand. Sachs is now overcome by the pain of his own renunciation. Eve consoles him, had Walther not been there, she would have chosen him. But Sachs replies that he would never have wanted to take on the role of Marke in Tristan and Isolde’s play.

This passage is the great renunciation of Hans Sachs. Overwhelmed by Eva’s words, he quotes the story of Tristan and Isolde, and the Tristan chord sounds in the orchestra.

O Sachs! Mein Freund! Du treuer Mann!

Synopsis: Now David and Margarethe have also entered in festive garb. Solemnly Sachs announces that Walther has created a masterpiece to whose baptism witnesses are needed; to this end he raises David to the rank of journeyman with a slap in the face.

Ein Kind ward hier geboren

The great quintet

Synopsis: The two couples and Sachs celebrate the birth of Walther’s prize song.

This intimate quintet is one of the absolute highlights of this opera and has a unique status in Wagner’s entire oeuvre. It is reminiscent of Beethoven’s quartet from Fidelio and is a skilful, magnificent resting place of this opera before the grand ceremony on the fairground. It begins with a solemn introduction by Hans Sachs accompanied by the most beautiful chords of the orchestra.

We hear this scene in two older recordings.

First with the heavenly Eva of Elisabeth Grümmer.

Selig wie die Sonne – Schöffler / Alsen / Kunz / Seefried / Dermota

Another version in a great recording with an absolute dream cast from 1931.

Selig wie die Sonne – Schumann, Melchior, Schorr, Parr, Williams

Synopsis: On Nuremberg’s fairground. The apprentice boys march up solemnly, ordered according to membership in their guilds.

Sankt Krispin lobet ihn – Sawallisch

The “Dance of the Apprentices”

Synopsis: The Apprentices happily perform a dance.

The “Dance of the Apprentices” boys is a well-known piece that is often heard in concert halls.

Tanz der Lehrbuben

The grand procession of the mastersingers

Synopsis: Accompanied by fanfares the Meistersinger march solemnly up.

The splendid procession of the Meistersinger is accompanied by a two-part choir of female and male voices.

Silentium

Synopsis: The people enjoy the day and celebrate their great poet Hans Sachs, who steps forward and looks at the crowd with emotion.

For Wagner, this scene was the quintessence of the opera: the calling to the German people to stand up for German art. The piece is a choral movement to a poem by the historical Hans Sachs with an elaborate polyphony of voices.

Wachet auf! Es nahet gen den Tag

Synopsis: Sachs welcomes the people and announces the contest. Beckmesser is visibly excited, constantly trying to remember the poem and desperately drying the sweat from his brow. Pogner now asks Beckmesser to start as the older one. Outraged, the people look at man, who seems to be too old for the young bride.

Euch macht ihr’s leicht, mir macht ihr’s schwer – Weikl

Beckmesser’s grotesque prize song

Synopsis: Beckmesser begins his song. But he muddles up the lyrics from the beginning. Astonished, the masters look at each other. As the words become more and more confused, the people break out in laughter. Irritated, Beckmesser continues, taking the text to the absurd. As everyone bursts into booming laughter, he falls on Sachs and explains that the words in fact and truth came from Sachs. Sachs now turns to the people and explains that the text was not written by him, but, mutilated by Beckmesser, by a real master. He asks the Meistersinger to admit this master to the competition. The masters give their consent and Sachs announces Walther von Stolzing.

The text that Wagner Beckmesser put in his mouth is both grotesque and comical: “lead juice and weight” is said at one point “on airy paths I scarcely hang from the tree” at another. Or even “the dog blew wavingly” in another verse.

Morgen ich leuchte im rosigem Schein – Werba

Walther’s prize song

Synopsis: Walther begins his song. Already after the first verse a murmur of astonishment goes through the audience and the mastersingers, which increases after the second verse. After the third verse there is no longer any doubt about the winner. Eva crowns the winner and Pogner solemnly accepts Walther into the guild of masters. But the latter rejects the consecration, shocked, Eve collapses.

Walther’s prize song consists of three verses that are continuously increased in tempo, volume and intensity. It is an urgent and romantic heroic tenor aria, which must be sung in the most beautiful legato and which receives its beauty not least through the magnificent accompaniment.

We hear in this effective piece Placido Domingo. The Spanish-speaking tenor was not the ideal Walther from an idiomatic point of view, but no tenor could match the beauty and splendor of his interpretation of the prize song.

Morgenlich leuchtend im rosigen Schein – Domingo

Honor your German masters

Synopsis: Now Sachs takes the floor and asks him not to despise the old masters, for new things can only grow on tradition. Sachs slips Walther over the master chain and Eva happily hurries to Walther. Pogner blesses the alliance and Walther lays his laurel wreath on Sachs’ head. The people enthusiastically join in Sachs’ words.

At the end of this extremely demanding act, Sachs has to mobilize his last reserves of strength for this performance and design the final speech written in high tessitura.

The people enthusiastically join in in a big scene, accompanied by the Meistersinger March.

Ehrt Eure deutschen Meister!

Dann bannt ihr gute Geister;

Honour your German Masters,

Then you will conjure up good spirits!

Verachtet mir die Meister nicht … Ehrt Eure deutschen Meister – Weikl

Recording Recommendation

CALIG, Thomas Steward, Sandor Konya, Gundula Janowitz, Thomas Hemsley, Brigitte Fassbaender under the direction of Rafael Kubelik and the Orchestra and Choir of the Bavarian Rundfunk.

Peter Lutz, opera-inside, the online opera guide on “DIE MEISTERSINGER VON NÜRNBERG” by Richard Wagner.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!