3 immortal pieces from the opera TRISTAN UND ISOLDE by Wagner- with the best interpretations from YouTube (Hits, Best of)

Wagner’s ambition was to compose the greatest love music that had ever been heard. To do this, he had to invent a new musical language for “Tristan and Isolde. He lived up to this claim and composed a work that, with its sensual, stirring chromaticism, was to exert a tremendous influence on the classical music world for the next almost 100 years.

The prelude

On Tristan’s ship on the high seas during the crossing from Ireland to Cornwall.

In order to understand Tristan musically, the overture already reveals to us Wagner’s most important thoughts. The overture begins with the use of the cellos, which sound the so-called suffering motif:

Even the first three notes of the suffering motive are characteristics of misfortune: the first leap to the long note is the minor sixth (the classical threatening interval) and the next leap is a minor second (the highest possible dissonance). Already in the third measure, the oboes sound the longing motive, whose beginning coincides with the end of the suffering motive:

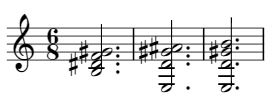

At this famous meeting of the two motifs, the legendary “Tristan chord” is heard, a chord with a strange floating dissonance that expresses neither pain nor joy, but a kind of ” indefinite search for resolution”:

But this dissonance is not resolved with the longing motive. And now the revolutionary thing happens, after about 1’30” a painfully sweet sequence erupts from the violins and violas in f, which again urgently tries to resolve itself:

But the resolution does not arise, for with the attainment of the target note another dissonance has appeared, and so on. Throughout the prelude, the music will seek the resolution of this strangely painful and uncertain dissonance and will not find it. It is, to use Wagner’s words, a “longing” whose desire is “insatiable and eternally renewed.” This unquenched longing will accompany the listener throughout the opera! Shortly after this passage, we encounter a related motif with the famous, concise seventh-note leap, which we will encounter again when Tristan and Isolde later look deeply into each other’s eyes, which is why it has been given the name “gaze motif”:

Again and again Wagner builds in chromatic dissonance chains to enhance the effect, as for example after about 2’30”:

We hear the overture in Wilhelm Furtwängler’s interpretation. His 1952 recording is considered the reference recording by most experts. Furtwängler is often called one of the great Wagnerians of the 20th century.

Ouvertüre – Furtwängler

The night song

Tristan leads Isolde to a flower-lined bench under a star-studded sky, and they invoke night and death as symbols of their love.

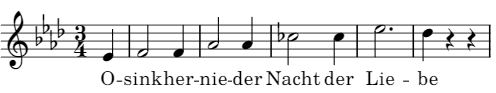

This so-called “Nachtgesang” begins with the most delicate chords of the muted strings and with an infinite melody in Tristan’s voice, the dreamlike night invocation motif:

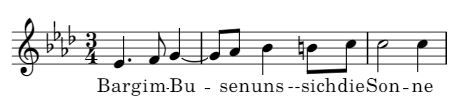

Now Wagner did something he always tried to avoid: the simultaneous singing of two voices, which in his opinion was unnatural. In the love duet, he has no other choice than the complete merging of the two lovers into “heilger Dämm’rung hehres Ahnen löscht des Wähnens Graus welterlösend aus”. Moved, Isolde then sings the dreamy melody of “Barg im Busen”:

Afterwards, this night music ends dreamily. Wagner uses part of his motifs for this passage from “Träume” the fifth of his Wesendonck-Lieder (on poems by Mathilde Wesendonck).

Margaret Price, the Isolde on Kleiber’s recording was a Mozart singer, her voice thus somewhat slimmer than that of a “highly dramatic soprano”. Together with Kollo, she brings an enchanting tender mood to this romantic passage, conducted by Kleiber with a long bow. The rapturous disappearance of the two voices at the end sounds especially beautiful.

O sink hernieder – Kollo / Price

The love death

Marke sees Isolde, who is standing next to Tristan’s deathbed. She is no longer responsive. Raptured, she has entered Tristan’s realm and her soul is leaving the world.

The so-called “Liebestod” is actually not a death, but as Wagner called the scene, a “transfiguration,” or as Isolde puts it, “Drowning – sinking – unconsciously highest pleasure!” («Ertrinken – versinken – unbewusst höchste Lust!»)

The opera fades away with the resolution of tension after four hours with the two famous B-flat major final chords.

Nina Stemme is the Isolde of our time. Listen to her grandiose transfiguration. Her voice has the penetrating power and warmth that makes the listener blissful.

Mild und Leise – Stemme

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!