The leitmotifs of the Wagner operas

In this opera guide, you will be introduced to the approximately 70 most important leitmotifs of the 10 great Wagner operas.

The leitmotifs stick the work together

The longer in the life of Wagner, the opera are no longer structured by arias and duets, the number opera gives way to the “Musikdrama”. As an important structural element and bracket of the four works, Wagner used leitmotifs that we encounter again and again in all four operas. Every important detail, be it persons or things (for example the camouflage helmet or the sword), has its musical formula. Wagner already used this technique in early works, and in the Ring it becomes the most important compositional principle. Ernst von Wolzogen, a student of Richard Wagner, worked out an overview of the motifs before the first performance of the ring in 1876 and gave them names (e.g. “Curse motif” or “Valhalla motif”). The number of leitmotifs is estimated at well over one hundred! The motifs (some of them only short phrases) are changed, interwoven with each other, create new motifs again and thus become the style-forming element of the ring. They serve the listener as motifs to remember, comment on the events on stage and point out connections. It is comparable with the role of the narrator, “who communicates with the audience above the heads of the characters” (Holland, opera leader). One also speaks of the semantization of music. Wagner tolerated Wolzogen’s statements but warned against reducing the work to the leitmotifs. Wagner himself called them “Errinerungsmotive” (Reminiscence motifs). In this opera guide we will present about three dozen of the most important motifs individually (in the portraits of the respective works).

Wagner’s orchestra experienced an enormous massing of instruments with the Ring and goes far beyond what is required for the Lohengrin, for example. However, Wagner’s aim was not volume, but a differentiation of tone colours in order to maximise the expressiveness and variation of the motifs.

Table of Content

♪ Der fliegende Holländer (The flying dutchman)

♪ Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg

♪ Götterdämmerung (Twilight of gods)

♪ Parsifal

Der Fliegende Holländer (The flying dutchman)

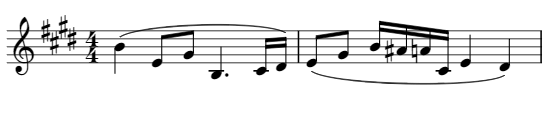

Dutchman-1A) Dutchman motif

The opera begins with one of Wagner’s incomparable overtures. The stormy sea is painted as in a symphonic poem. Rossini’s and Meyerbeer’s storms are only a gentle breeze compared to Wagner’s hurricane. We hear three important leitmotifs in this opening piece. Right at the beginning we hear the Dutchman motif:

Dutchman-1B) Ghost motif

Shortly thereafter the concise ghost motif:

Dutchman-1C) Redemption motif

After this section we hear a lyrical theme, the so-called redemption motif

Dutchman-1D) love motif

And shortly afterwards the love motif, which will then also later conclude the overture:

1) Overture – Klemperer / Philharmonia

Tannhäuser

TANNHÄUSER-1A) Faith motif

In the overture we encounter three important leitmotifs. The first is heard right at the beginning and opens piano in the winds. It reflects faith and is also heard in the famous pilgrim chorus of the third act:

TANNHÄUSER-1B) Repentance motif

After about a minute, passionate strings sound; it is Tannhäuser’s repentance motif:

TANNHÄUSER-1C) Bacchanal-/Lust motif

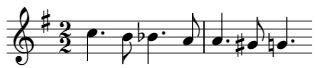

After about 4 ½ minutes, a playful motif suddenly breaks in. It is the Bachanal or lust motif:

1) Overture – Furtwängler

Lohengrin

LOHENGRIN-1A) Grail motif

The Grail motif is already heard in the overture. In Elsa’s dream narrative, it is heard again (in the sound sample at 2:20):

LOHENGRIN-1B) LOHENGRIN motif

In the winds we hear the Lohengrin motif (2:50):

LOHENGRIN-2B) forbidden question motif

Tristan und Isolde

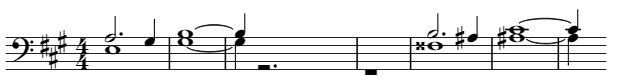

Tristan-1A) Suffering motif

In order to understand Tristan musically, the overture already reveals to us Wagner’s most important thoughts. The overture begins with the use of the cellos, which sound the so-called suffering motif. Even the first three notes of the suffering motive are characteristics of misfortune: the first leap to the long note is the minor sixth (the classical threatening interval) and the next leap is a minor second (the highest possible dissonance):

Tristan-1B) Longing motif

Already in the third measure, the oboes sound the longing motive, whose beginning coincides with the end of the suffering motive:

Tristan-1C) Tristan chord

At this famous meeting of the two motifs, the legendary “Tristan chord” is heard, a chord with a strange floating dissonance that expresses neither pain nor joy, but a kind of “indefinite search for resolution”:

Tristan-1D) GAZE motif

1 or 2 minutes later, we encounter a related motif with the famous, concise seventh-note leap, which we will encounter again when Tristan and Isolde later look deeply into each other’s eyes, which is why it has been given the name “gaze motif”:

1) Ouvertüre – Furtwängler

Tristan-2A) Death motif

After the sailor’s song we hear Isolde, who is tormented by deep black thoughts. When she expresses death wishes, the death motif is heard:

2) Frisch weht der Wind – Nilsson

Tristan-3A) wounded Tristan motif

Isolde begins the narrative of the “wounded Tristans” with the motif of the wounded Tristan, which is played repeatedly in the orchestra:

Tristan-3B) Anger motif

When she tells us that she took pity on him, one hears both the longing motif and the motif of the failing Tristan, which together create a poignant effect. But then the thoughts wander back to her humiliation and the rushing anger motif emerges in the low strings:

3) Weh, ach wehe dies zu dulden – Nilsson / Ludwig

Tristan-4A) love call motif

The prelude announces the next scene in terms of content. After a painfully dissonant opening chord, we hear busy eighth-note movements in the violins after a few measures, which soon lead to a new important motive in the flutes that will become the basis of all the love motives to come, the love call motive, here played at a fast tempo:

Tristan-4B) Bliss motif

Gradually the desire becomes more urgent and we hear in the violins and woodwinds the bliss motive, which with its downward urging character is related to the love call motive:

4) Einleitung (Introduction) – Kleiber

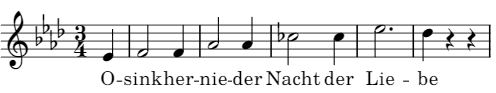

Tristan-5A) Night invocation motif

This so-called “Nachtgesang” begins with the most delicate chords of the muted strings and with an infinite melody in Tristan’s voice, the dreamlike night invocation motif:

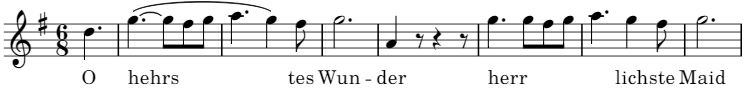

5) O sink hernieder – Kollo / Price

Tristan-6A) love death motif

Accompanied by heavy brass, Tristan speaks of dying together and we hear the love-death motif for the first time:

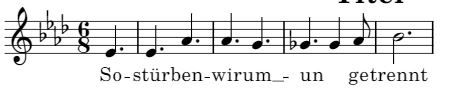

6) So starben wir – Melchior / Flagstadt

Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg

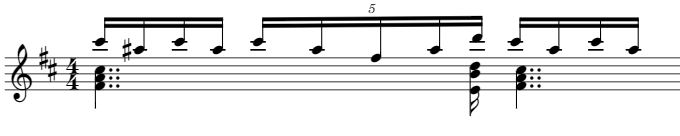

MEISTERSINGER-1A) MEISTERSINGER motif

The magnificent prelude has become one of Wagner’s most famous concert pieces. Wagner introduces some of his wonderful leitmotifs and lets them shine polyphonically in the orchestral parts. We get to know five of the most important leitmotifs of the opera. At the beginning we hear the Meistersinger motif in radiant C major, which portrays the dignity and sublimity of the masters:

MEISTERSINGER-1B) love motif

Next, Walther’s urgent love motif is heard, with the falling fourths (which will reappear in the Beckmesser caricature):

MEISTERSINGER-1C) MEISTERSINGER march motif

Shortly afterwards, the Meistersinger March appears, a fanfare-like theme that Wagner took from a historical Meistersinger songbook

MEISTERSINGER-1D) Guild motif

And immediately after that we hear the guild motif:

MEISTERSINGER-1E) Passion motif

After a longer transition we hear the tender and expressive Passion motif, which later becomes part of the price song.

1) Vorspiel (Prelude)

MEISTERSINGER-2A) BECKMESSER motif

After tuning the lute you hear the Beckmesser motif:

Remarkable are the pitiful falling fourths, which only seem like a miserable caricature of the falling fourths of Walther’s radiant love motif (compare the leitmotif in the section on prelude).

2) Den Tag seh ich erscheinen – Weikl

MEISTERSINGER-3A) Renunciation motif

The monologue begins with Sachs’ renunciation motif in the strings:

RHEINGOLD-1B) Rhine motif

After 2 minutes the motif changes into a wavy melody representing the river Rhine flowing lazily along. It is the Rhine motif that presents the world in its natural order.

1) Vorspiel – Solti

RHEINGOLD-2A) RHEINGOLD motif

The beauty of gold shows the world in its natural order, unclouded by any domination. The Rhinemaidens as its keepers are not subject to any power. They sing of the hoard (the treasure) with the so-called Rhinegold motif:

RHEINGOLD-2B) Gold motif

After a few bars, the trumpets sound the gold motif. The motif is always accompanied by shimmering strings and/or harps, which describe the flickering of gold:

RHEINGOLD-2C) renunciation motif

The Rhinemaidens reveal the secret of the gold:

Only he who fosears lovs’power, only he woho fofeits love’s delight,

Only he can attain the magic to fashion the gold into a ring

In the German text: “Nur wer der Minne Macht entsagt, nur der love Lust verjagt, nur der erzielt sich den Zauber, zum Reif zu zwingen das Gold.”

We hear in this scene the so-called renunciation motif. The motif is heard in the trombones and Wagner tubas, which gives the motif a special, dark timbre:

2) Lugt, Schwestern! Die Weckerin lacht in den Grund (Rheingold! Rheingold!)

RHEINGOLD-3A) Ring motif

In the transition music to the next scene another motif emerges, it is the ring motif.

3) Orchesterzwischenspiel – Böhm

RHEINGOLD-4A) WALHALLA motif

In the orchestra we hear a motif that will accompany the listener through all 4 evenings. It’s the Valhalla motif.

4) Wotan, Gemahl, erwache – Flagstadt / London

RHEINGOLD-6A) NIEBELHEIM motif

The scene changes, the light becomes dark and the music merges seamlessly into the realm of the Nibelungs. The dwarfves of the Nibelungs live in simple dwellings under the earth, where they mine the ores of the ground in drudgery.

6) Orchesterzwischenspiel – Janowski

RHEINGOLD-7A) Curse motif

Wotan considers himself now safe from danger. He could kill several birds with one stone. He was able to break Alberich’s power, he got the gold to pay the giants and he is in possession of the ring that gives him the power. He doesn’t take the curse Alberich is casting seriously:

„Wer ihn besitzt, den sehre die Sorge, und wer ihn nicht hat, den nage der Neid“.

«Whoever possesses it shall be consumed with care, and who ever has it not be gnawed with envy.»

The curse motif is heard in the orchestra:

7) Bin ich nun frei? – Brecht

RHEINGOLD-8A) ERDA motif

When Erda appears, the music changes its character. A mystical motif sounds, the so-called Erda motif. It is related to the natural motif (which we heard in the prelude), but sounds at a measured tempo and in a minor key.

Weiche Wotan Weiche – Madeira

Die Walküre

WALKÜRE-1A) Sword motif

Siegmund begins his great monologue “ein Schwert hiess mir der Vater” (My father promised me a sword). Proudly, the sword motif soon resounds in the winds:

1) Ein Schwert hiess mir der Vater – Kaufmann

WALKÜRE-2A) love motif

The short prelude to the second act begins with reminiscences from the first act. First we hear the sword motif, which merges into the love motif of Sieglinde and Siegmund:

WALKÜRE-2B) Ride of the Valkyries motif

Next we hear the motif of the Ride of the Valkyries for the first time. After Wotan’s entrance we hear the famous battle cry of the Valkyries “Hojotoho”.

2) Nun zäume dein Ross, reisige Maid – London / Nilsson / Leinsdorf

WALKÜRE-3A) Fate motif

This section describes the first meeting of a divine and a human figure. Brünnhilde, the goddess of war, feels pity for the first time, a feeling previously unknown to her. To underscore the significance of the moment, Wagner prominently employs the so-called “Wagner tubas,” which were specially constructed for the Ring. In a solemn, measured tempo, Brünnhilde appears to Siegmund like an angel of death, and the tubas play you the poignant motif of fate.

WALKÜRE-3B) Death announciation motif

This motif of fate forms the basis for the second important motif, which remains present throughout the scene:

3) Sieh auf mich – Nilsson / King

WALKÜRE-4A) SIEGFRIED motif

In this dramatic scene, in which the pregnant Sieglinde desperately seeks shelter, Brünnhilde reveals to her that the fruit of her love for Siegmund will be a hero; gloriously, the Siegfried motif resounds for the first time:

WALKÜRE-4B) Love Redemption motif

She then hands Sieglinde the remains of Siegmund’s sword. Brünnhilde is now overcome with emotion over Brünnhilde’s selflessness and she sings over the most colorful orchestra, the radiant love redemption motif. We will not encounter this motif again until the end of the Ring; it will conclude the Twilight of the Gods and thus the entire work:

4) So fliehe denn eilig und fliehe allein! – Nilsson / Brouwenstijn

WALKÜRE-5A) resting place motif

Wotan’s farewell to Brünnhilde is one of the great scenes of the Ring. Listen to how Wotan, tenderly moved, says goodbye to Brünnhilde and the music dissolves in an ecstatic conclusion. This musical section is marked by many leitmotifs. First we hear the nostalgic resting place motif:

WALKÜRE-5B) Wotan’s love motif

Then we hear the Siegfried motif in the horns («Denn einer nur freit die Braut, der freier als ich, der Gott»). It is followed by Wotan’s love motif (from 2:55), which expresses the pain of parting. It appears first in the winds and then, in an overwhelming gesture of pain, in the violins:

WALKÜRE-5C) Spear motif

The long lyrical scene in which Wotan puts Brünnhilde to sleep ends abruptly with the spear motif with which Wotan moves to action:

WALKÜRE-5D) Magic fire motif

With the magic fire motif, Wotan, with the help of Loge, lights the fire around Brünnhilde’s sleeping place:

5) Leb wohl du kühnes herrliches Kind – London / Leinsdorf

Siegfried

SIEGFRIED-1A) NIEBELHEIM motif

Haunting timpani in piano and two pale chords forming a diminished seventh introduce the prelude. They probably symbolize Mime’s despair at his inability to forge the sword. From this develops the busy Nibelheim motif, the hammering work of the forge, which we know from Rheingold:

SIEGFRIED-1B) Treasure motif

Then Wagner combines two other motifs with the Nibelheim motif. On the one hand the Fronarbeit motif (a falling second) and the Treasuremotif:

1) Vorspiel – Solti

SIEGFRIED-2A) Siegfrieds horn motif

With the motive taken from the horn, Siegfried sings a cheerful “Hoiho!” upon entering Mime’s dwelling. It contrasts with Mime’s chromatic, somber tonal world through its tonal leap. A little later, we hear Siegfried’s motif taken from nature played in the horn:

2) Hoiho! Hoiho!

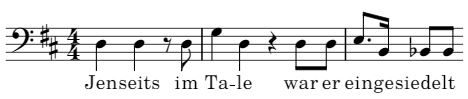

SIEGFRIED-3A) MIME motif

Mime’s name is descriptive, it means something like “pretend”. Wagner does not see Mime as a creative spirit (as a true artist), even the magic helmet could only be created under Alberich’s supervision. He does not have the greatness of the gods and is a selfish man. In his opening narrative, we hear his unsympathetic and awkward Obstinato motif in the basses.

3) Als zullendes Kind zog ich Dich auf – Svanholm

SIEGFRIED-4A) WANDERER motif

With solemn chords, Wotan enters Mime’s cave. It is the so-called Wanderer motif. As befits a god, they are solemn, measured chords, which in their major form stand out from the world of Mime.

4) Heil dir weiser Schmied

SIEGFRIED-5A) Dragon motif

The fact that the giant Fafner has turned into a dragon is no coincidence. With this, Wagner wants to show that whoever is in possession of gold turns into a monster. The prelude begins with the theme of the dragon Fafner:

5) Vorspiel

SIEGFRIED-6A) Siegfried’s Horn Ruf motif

On the horn we hear 2 important leitmotifs of Siegfried. The first is lyrical. The second is of a heroic nature:

6) Haha! Da hätte mein Lied! – Windgassen

SIEGFRIED-7A) Love lust motif

When with Mime his only point of reference is dead, Siegfried feels infinitely lonely. Soon he falls into a nostalgic mood and a yearning love-lust motif resounds, becoming more and more urgent:

7) Da liegt auch du, dunkler Wurm! – Windgassen / Sutherland

SIEGFRIED-8A) Awakening Brünnhilde motif

This scene is one of the greatest scenes in the entire Ring! Brünnhilde’s awakening motif sounds. This beautiful motif of the awakening Brünnhilde shows how Wagner knew how to form great things from 2 simple chords. He lets the E minor chord swell and decay in the winds and picks up the note again only in the winds in a crescendo and lets it play around with the harps. The harp arpeggios unmistakably recall the awakening of nature at the beginning of the Ring in the prelude to Rheingold.

8) Heil dir, Sonne! Heil dir, Licht! – Evans

SIEGFRIED-9A) Extasy motif

Accompanied by the love-ecstasy motif, Brünnhilde greets Siegfried:

9) O Siegfried! O Siegfried! Seliger Held!

SIEGFRIED-10A) Eternal love motif

Brünnhilde asks Siegfried to keep her divine virginity. Dazu hat er ein wunderschönes Motiv komponiert. Dieses “Ewige-love” Motiv hat Richard Wagner auch im Siegfried-Idyll verwendet (siehe weiter unten).

10) Ewig war ich, ewig bin ich – Nilsson / Windgassen

Götterdämmerung (Twilight of gods)

GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG-1A) Siegfried’s hero motif

Brünnhilde wakes Siegfried, and his heroic motif resounds jubilantly in the brass:

1) Zu neuen Taten – Jones / Jung

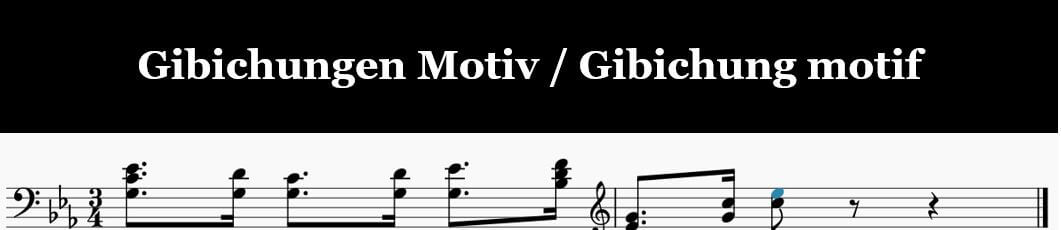

GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG-2A) Gibichung motif

We are in the realm of the Gibichungs. In the ring they represent the normal mortal humans, who, with the exception of Hunding, have not yet appeared in the ring before. Their highest representatives, Gutrune and Gunther, become tragic figures in the Twilight of Gods – the deceived cheats. In the end they are mediocre creatures, almost anti-heroes, with whom one feels no pity. Wagner wrote for them the proud, but somewhat simple “motif of the Gibichung”.

2) Nun hör, Hagen, sage mir, Held …

GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG-3A) Friendship motif

We hear the honest, heartfelt friendship motif of Gunther in the strings:

GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG-3B) Gutrune’s motif

We hear Gutrune’s motif right at the beginning. Like her brother’s friendship motive, it begins with a downward jump of a fifth:

3) Willkommen Gast… Vergäss ich alles, was Du mir gabst – Jung / Mazura / Altmeyer

GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG-4A) Murder motif

In the prelude, a pale and restless music transports us into the world of Alberich. Alberich proposes to Hagen that he destroy Siegfried (“Den goldnen Ring, den Reif gilt’s zu erringen!”):

4) Vorspiel … Schläfst du, Hagen, mein Sohn – von Kannen / Kang

GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG-5A) Götterdämmerung motif motif

Once again Wagner quotes many of the ring’s leitmotifs. As the ravens fly away, we hear the tragic Twilight of Gods motif:

5) Zurück vom Ring – Boulez

Parsifal

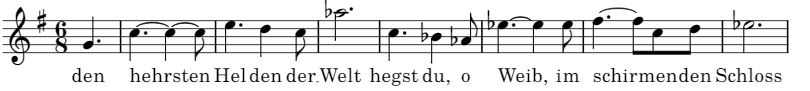

PARSIFAL-1A) love feast motif

Right at the beginning, the “love feast motif” is heard, an expansive theme:

The syncopated form is particularly striking; there is no sense of meter and a feeling of rapture, of floating. Wagner himself called it the central musical theme of this work. It will become the musical motif of the communion ritual of the finale of Act 1. Wagner created with this long theme a (in Wagner’s words) “basic theme,” in the sense that it can be broken down into three parts, each of which becomes a new motif again! We find the first part in the Grail motif, the second (minor) part becomes the pain motif and the third part becomes the spear motif.

PARSIFAL-1B) Grail motif

After 3 times appearance of the love feast motive, we hear the so-called Grail motive, another central leitmotif of this work:

PARSIFAL-1C) Faith motif

Right after that we hear the third important motif of the prelude. It is the short but powerful motif of faith:

1) Vorspiel – Knappertsbusch

PARSIFAL-2A) Suffering motif

For Wagner, Amfortas’ role was central. He compared his suffering “with that of the sick Tristan of the third act with an increase” (letter to Mathilde Wesendonck). Everything in this work revolves around his redemption by Parsifal. When he arrives, we hear his motif:

PARSIFAL-2B) Morning splendor motif

The prospect of cooling offf, the pain relief and the radiant nature of Montsalvat defies the suffering Amfortas with a beautiful theme, the so-called morning splendor motif:

2) Recht so! Habt Dank – van Dam / Hölle

PARSIFAL-3A) Angelic motif

The great narrative of Gurnemanz reveals to us three further central musical motifs. When Gurnemanz tells deeply stirred the story of how Titurel once received the chalice and spear, the angelic motif is heard, which is related to the faith motif:

PARSIFAL-3B) KLINGSOR motif

When Gurnemanz comes to talk about Klingsor, the mood changes and the Klingsor motif is heard:

PARSIFAL-3C) AMFORTAS motif

It is a motif that is not magnificent, but offers a strange shadowing and is related to the Amfortas motif, as the foll shall provide Amfortas with the longed-for redemption by recapturing the spear.

3) Titurel, der fromme Held, der kannt’ ihn wohl

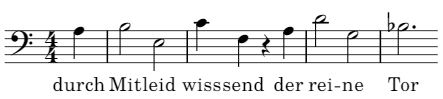

PARSIFAL-4A) PARSIFAL motif

Parsifal, appears with the motif that bears his name:

Because Parsifal is still a fool in this scene, his motif sounds inconspicuously; only in its radiant form will it resound jubilantly in the horns in the third movement.

Weh, Weh! Wer ist der Frevler – Hoffmann / Moll

PARSIFAL-5A) Bell motif

As Gurnemanz and Parsifal make their way to the castle, the magnificent transformation music is heard, introduced by the bell motif:

5) Verwandlungsmusik (Transition music) – Karajan

[/av_image]Accompanied by pathetic brass, Gurnemanz then performs the unction

5) Gesegnet sei, du Reiner – Sotin / Hoffmann

PARSIFAL-5A) Flower meadow motif

Wagner called this famous scene, which takes place after Kundry’s baptism, “Good Friday spell,” which, like the Waldweben, is an orchestral interlude inspired by Beethoven’s Pastorale. It is characterized by the so-called flower meadow motif, which is played by the oboe and describes the graceful colors, shapes and scents of the forest and meadow:

Wie dünkt mich doch die Aue heute schön – Thomas / Hotter

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!