Munich and Bavaria: A travel guide for music fans

Visit destinations related to classical music and opera art and historical reference. Get to know exciting ideas and background information.

0

GOOGLE MAPS - OVERVIEW OF DESTINATIONS

Here you will find the locations of all the destinations described on Google Maps.

0

1

LIFE AND WORK OF ARTISTS IN MUNICH AND BAVARIA

The lives and works of Bruckner, Liszt, Mozart, Strauss and Wagner in Munich and Bavaria.

1

2

CONCERT HALLS AND OPERA HOUSES

The most historically significant performance venues.

2

3

MUSEUMS

The museums in honour of Liszt, Wagner and Strauss.

3

4

CEMETERIES AND TOMBS OF FAMOUS MUSICIANS

Gravesites of famous musicians buried in Bavaria.

4

5

CHURCHES

The church of Seeon Monastery. Where the young Mozart often went.

5

6

MONUMENTS AND MISCELLANEOUS

Other historical landmarks related to composers.

6

GOOGLE MAPS – OVERVIEW OF DESTINATIONS

Zoom in for destinations

COMPOSERS IN MUNICH AND BAVARIA

Anton Bruckner in Munich

Bruckner visited Munich because of Richard Wagner

Anton Bruckner, who was living in Vienna then, visited Munich eight times. It was in this city that he experienced one of the great moments of his life in 1885, when the munich orchestra Munich became the second city to perform his Seventh after its lukewarm reception in Leipzig, and it was received triumphantly by the audience. At the celebration the next day, the conductor Hermann Levi called it the most important symphony after Beethoven, which was, in Bruckner’s own words, one of the greatest satisfactions of his life for him, who was often offended and overawed.

During these days, Bruckner also sat with the painter von Kaulbach for the portrait, which Bruckner, however, did not consider to be very successful.

The first encounter

Another great day had occurred for Bruckner in Munich when he met his idol Richard Wagner for the first time in 1865 on the occasion of the first performances of “Tristan und Isolde”. Wagner later spoke of the great symphonist Bruckner, but maintained a somewhat condescending attitude toward the somewhat “doltish” Bruckner.

The last time Bruckner saw the revered master was at the Villa Wahnfried after the first performance of “Parsifal,” and he asked him “Well, Bruckner, what do you say to Parsifal?” Bruckner knelt down in front of him and stammered: «Meister, i bet Ihna an!» (Master, I adore you!)

der Erstaufführung des «Parsifal», und der fragte ihn «Na, Bruckner, was sagen Sie zum Parsifal?» Bruckner kniete sich vor ihm nieder und stammelte: «Meister, i bet Ihna an!»[/sc_fs_faq]

TO THE COMPLETE BRUCKNER BIOGRAPHY

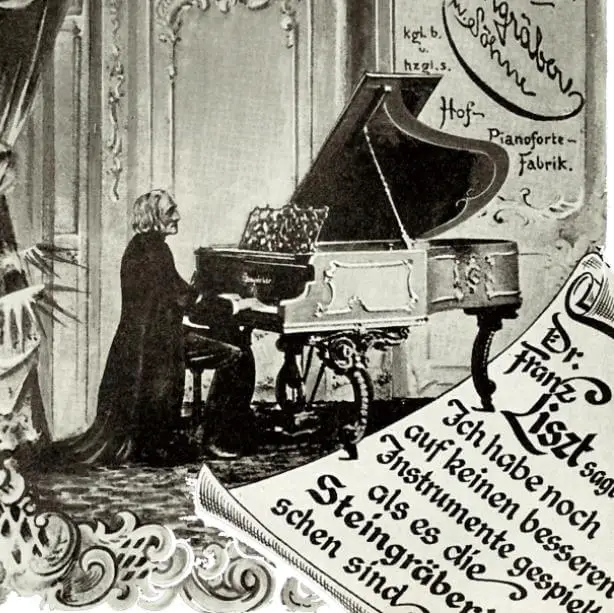

Franz Liszt in Bayreuth

Liszt was in Bayreuth a little more than a dozen times. The reason for visiting was, of course, Richard and Cosima’s festival house, but also his relationship with the Bayreuth pianofactory Steingraeber (more on this below).

The chequered relationship with Wagner

Liszt’s relationship with Wagner dates from the late forties, where Liszt began to promote Wagner with performances and financial contributions. The relationship with him was friendly, but became strained with his daughter’s extramarital affair with Wagner. This was a thorn in the side of the devout Liszt (which, however, was never an obstacle for him personally…).

Later the relationship improved again and the Wagners tried to engage the famous pianist with concerts and occasions for the festival, which Liszt occasionally complied with. Wagner was always scowling during Liszt’s visits, probably because he was jealous of Liszt’s popularity. Wagner often spoke ill of Liszt’s music, but on several occasions had “stolen” ideas from his works, for example in Parsifal (transformation music).

Death in Bayreuth

After Wagner died in 1883, his daughter Cosima took over the responsibility for the festival and again she called for Liszt, because the pressing financial obligations weighed on her and she wanted to make use of her father’s glamorous name once again. However, she did not want the now infirm man in the Villa Wahnfried and put him up in the house next door. When Liszt arrived, he was already seriously ill. Nevertheless, he patiently attended the events. Towards the end of July he became bedridden, but Cosima had little time to care for her father. So he died lonely in his room of pneumonia, not even the last rites could be received by the faithful Abbé Liszt. Cosima kept Liszt’s death a secret until the festival was over. For prestige reasons, she ignored Liszt’s wish to be buried in Hungary and had him buried in Bayreuth (though there is a major controversy about this). The funeral mass in the Catholic church in Bayreuth was attended by 2000 people, Cosima did not think it necessary to be there.

Franz Liszt with daughter Cosima:

ZUR VOLLSTÄNDIGEN BIOGRAPHIE VON MOZART

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in Munich

Premiere of his Idomeneo

Mozart was in Munich eight times. At the age of six, he already gave concerts in the bavarian capital with his sister Nannerl. 1775 also saw the premiere of the commissioned work “La finta Giardiniera” (in the opera house St. Salvator). Particularly significant was his stay of several months during the rehearsals of “Idomeneo”.

Mozart’s father and his sister Nannerl proudly sat in the Cuvilliés Theater in Munich (where the Residenztheater stands today) on January 29, 1781, for the premiere of this magnificent opera seria. But the success was not great enough to jump-start Mozart’s career. Although the prince was satisfied, Mozart missed his goal of becoming Kapellmeister in Munich and gaining independence from the Salzburg court.

TO THE COMPLETE MOZART BIOGRAPHY

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in Seeon

The organ of the monastery

Mozart visited this former monastery several times in his youth, the first time as a nine-year-old when his father was traveling from Salzburg to Munich Here he composed and played the organ.

TO THE COMPLETE MOZART BIOGRAPHY

Richard Strauss in Munich

A true Munich native and his connection to a Munich brewery

Richard Strauss was born in Munich in 1864 into a musical family. His father was a well-known horn player of the Munich Court Opera, who became known as an orchestral musician through his not unclouded relationship with Richard Wagner. On his mother’s side, Richard was related to the Pschorr family, co-owners of the long-established Hacker-Pschorr brewery.

The relationship between the city of Munich and its famous son can be described as undercooled. A plaque referring to his vanished birthplace in a parking garage is eloquent testimony to this.

Strauss was a child prodigy and began composing at age 6. He wrote his Opus 1, a festive march for large orchestra, when he was only 12. In 1882 he began studying philosophy and art history at the University of Munich, but soon dropped out to devote his professional life to music. His first works were performed at the age of 19.

Richard left Munich at the age of 20 when he met Hans von Bülow, who brought him to the theater in Meiningen.

At the age of 22 he returned to the Court Opera as third Kapellmeister. After a trip to Italy, he wrote the first symphonic poem (Aus Italien) and began composing “Don Juan” and “Tod und Verklärung”. After a dispute, he left Munich again for Weimar

Definitive departure

In 1894 he returned as Kapellmeister, but soon left Munich permanently in anger when he was not considered for the succession of the late director of the Court Opera, Hermann Levi. His relationship with Munich soured and his most important cities artistically became Dresden, Berlin and Vienna

He only reconciled with his hometown in his old age (see below under Destination Bavarian State Opera).

His last appearance in Munich in 1949 was particularly impressive when he conducted the second act of his Rosenkavalier at the Prinzregenten Theater.

TO THE FULL BIOGRAPHY OF RICHARD STRAUSS

Richard Strauss in Bayreuth

The encounter with Wagner

Richard Strauss had an intense relationship with Bayreuth. His father was a horn player in the Munich Court Opera and played in the premieres of “Meistersinger” and “Tristan” in Munich and was frequently in Bayreuth with the orchestra. He was a sharp-tongued critic of Richard Wagner and fought many a battle with the composer. For example, he sat as the first horn player in the orchestra during rehearsals for “Meistersinger” and once even organized a strike after a particularly long day of rehearsals. Wagner took it with humor, saying, “Old Strauss may be an obnoxious fellow, but when he blows the horn, you can’t be mad at him.”

Strauss’s father took his son to Bayreuth in 1882 to see a performance of Parsifal as a reward for passing his Abitur exams, and it was there that Richard met the master in person. Strauss subsequently became an ardent Wagner devotee.

The changing relationship with the Wagners

Strauss subsequently became an ardent Wagner supporter. He befriended Cosima and in 1889 became assistant conductor to Hans von Bülow. Cosima recognized Strauss’s potential and even wanted to pair him with her daughter Eva, and in 1894 he was allowed to conduct the Tannhäuser premiere in Bayreuth (with his future wife Pauline as Eva).

The once friendly relationship between Cosima Wagner cooled with Strauss’ opera Salome, about whose musical style Cosima was not at all edified (“an opera about a Jewish girl”). Later the two made up, and Strauss stepped in as conductor in 1933’s “Parsifal” when Toscanini left Bayreuth in a rage.

Strauss with Winifred Wagner and others in front of Villa Wahnfried:

TO THE FULL BIOGRAPHY OF RICHARD STRAUSS

Richard Strauss in Garmisch

In 1908 Strauss moved into the newly built house in rural Garmisch-Partenkirchen, financed with the proceeds of his “Salome“. The villa served first as a summer retreat and later as a residence, in whose study most of the works from “Elektra” onward were written.

His home of the second half of life

In the twenties he was on the road a lot (Dresden, Vienna, Salzburg and tours), and in the Nazi years he took over the office of Reichsmusikdirektor at the beginning. Strauss’s role in World War II was ambivalent. Strauss was not an anti-Semite, but he was opportunistic at best. When the American troops marched into Garmisch, Strauss received them in his garden, certificates in hand, and was thus able to protect his house from requisition “as the composer of the Rosenkavalier.”

After the Second World War, Strauss, who was in poor health and financially strapped, left Garmisch for Switzerland for fear of denazification, where he was supported by patrons and lived in hotels.

Finally, he returned to his beloved house and died there in 1949.

TO THE FULL BIOGRAPHY OF RICHARD STRAUSS

Richard Wagner in Munich

His rescuer comes from Munich

Richard Wagner was completely penniless in 1864 after his Tristan fiasco in Vienna What he did not know was that Ludwig II left the theater in 1861 after a performance of Lohengrin, deeply moved and in tears.

When he called Wagner to Munich in this fateful year of 1864, he rescued the composer from his greatest life crisis. He subsequently became his patron. However, Wagner’s exorbitant demands placed an excessive burden on the state coffers, and in 1865 Wagner had to leave Munich against the king’s will under pressure from the royal government.

LINK TO THE COMPLETE WAGNER BIOGRAPHY

Richard Wagner in Bayreuth

His lifelong dream

Wagner’s lifelong dream was to build his own festival house, where he could realize the Gesamtkunstwerk (Total Work of Art) – the unification of the arts of music, architecture, theater and stage design. Wagner chose this provincial town in order to be able to give maximum attention to the performances during the festival without the distractions of a big city.

It was clear to Wagner from the beginning that the performance of such a work was hardly possible in the existing theater landscape.

The idea of a festival theater was born early on. But it was to take another 25 years before it was completed. Securing the financing for this enormous undertaking cost Wagner a lot of work. In 1872, he moved to Bayreuth with his wife Cosima, and construction work began. Together with many patrons, he succeeded in raising money for the laying of the foundation stone for the Festspielhaus and for the purchase of Villa Wahnfried. The raising of capital to finance the Festspielhaus was slow and he had to travel a lot, giving lectures and conducting, and his heart was badly affected. Once again Ludwig helped him out of a jam with a considerable amount of money. Fortunately, he had a group of young artists around him who helped him with various tasks, and the group was given the nickname “Nibelungenkanzlei”.

Four years later, the Festspielhaus was opened with Rheingold. The first festival took place in 1876 in the presence of Wilhelm and all the European cultural celebrities and became Wagner’s greatest triumph. However, this first festival was a financial fiasco, which made it take six years until the next festival in 1882, where Wagner premiered his last work, “Parsifal”.

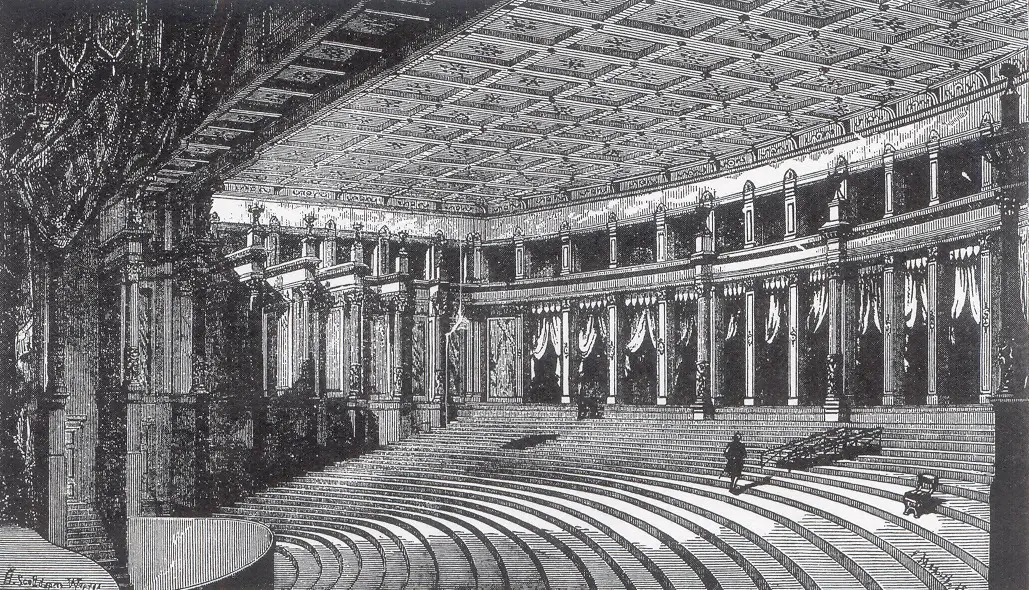

The Festspielhaus from the inside:

LINK TO THE COMPLETE WAGNER BIOGRAPHY

CONCERT HALLS AND OPERA HOUSES

Bavarian State Opera I

Ballett and Opera

The State Opera was opened in 1817 as the Court Opera. It was severely damaged three times, after two major fires and the damage from the Second World War. Today, the Munich National Theatre is home to the Bavarian State Opera, the Bavarian State Orchestra and the Bavarian State Ballet. It seats 2100 spectators.

Bavarian State Opera II

Wagner und Strauss

Es war Uraufführungsort von «Tristan und Isolde», «Meistersinger von Nürnberg», «Die Walküre» und «Rheingold». Letztere beide wurden gegen den Willen und in Absenz Wagners durchgeführt.

It was the premiere venue for “Tristan und Isolde,” “Meistersinger von Nürnberg,” “Die Walküre” and “Rheingold.” The latter two were performed against Wagner’s will and in his absence.

Only Strauss’ twelveth opera was premiered in his hometown. Strauss was offended that he was passed over for the post of general music director in 1886. He even wrote a reckoning with his hometown with his opera “Feuersnot”. Strauss was offended that he was passed over for the post of general music director in 1886. He even wrote a reckoning with his hometown with his opera “Feuersnot”. Only when his friend Clemenss Krauss (presumably through Hitler’s mediation) took over the direction of the Munich Opera did two premieres take place there (Friedenstag in 1938, and Capriccio in 1942).

Richard Strauss:

Gasteig München

A special relationship with Bruckner

With the 7th Symphony, Munich established an important Bruckner tradition. First it was Hermann Levi, then Ferdinand Löwe, who led Bruckner’s work to flower. The tradition was passed on to the legendary Celibidache concerts in the Gasteig. Among others, the Gasteig opened in 1985 with Bruckner’s 5th. Ghergiev also maintains the Bruckner tradition in our days.

Gasteig Concert hall:

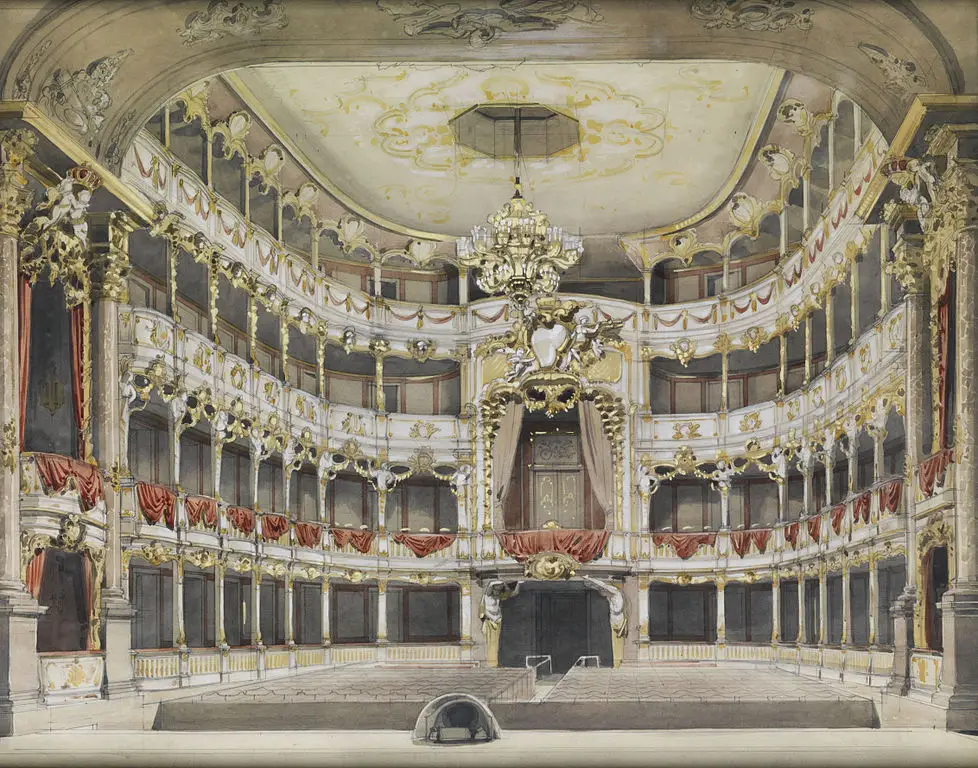

Cuviliés Theater Munich

Premiere site of Mozart’s Idomeneo

The Cuvilliés Theater, site of the first performance of “Idomeneo”, was destroyed during World War II and rebuilt from scratch. Fortunately, a considerable part of the interior furnishings were dismantled in a daring action before the aerial bombs did their terrible work. With the rescued interior parts, a new Cuvilliés Theater was created elsewhere, which can be visited and is considered the most beautiful rococo theater in Germany.

Reproduction of the Cuvillié Theater from the 19th century:

Festspielhaus Bayreuth

The theatre for Wagner’s Gesamtkunstwerk (Total work of Art)

It was clear to Wagner from the very beginning, that the performance of such a work like “The ring of the Nibelung” in existing theatres was hardly possible. Early the idea of his own festival theatre was born. But it was to take another 25 years until its completion. Securing the financing of this enormous undertaking cost Wagner a great deal of work. In 1872 Wagner and his wife Cosima moved to Bayreuth, and construction work began. Together with many patrons he succeeds in raising money for the laying of the foundation stone of the Festspielhaus and for the purchase of the Villa Wahnfried. Four years later the Festspielhaus is opened with Rheingold. The first festival took place in 1876 in the presence of Emperor Wilhelm and all the European cultural celebrities and became Wagner’s greatest triumph of his entire life.

With the Ring and the construction of the Festspielhaus, Wagner completed his vision of the Gesamtkunstwerk: the union of the arts of music, poetry, architecture and stage design. The Festspielhaus still impresses with its excellent acoustics and view of the stage and the covered orchestra pit.

Festival Tickets must be obtained in advance over the long term. Guided tours are offered selectively.

Festival Tickets must be obtained in advance over the long term. Guided tours are offered selectively.

https://www.bayreuther-festspiele.de/

Festspielhaus:

Other opera venues in Bavaria

MUSEUMS

Villa Wahnfried / Richard Wagner Museum Bayreuth

From 1874 Bayreuth and the Villa Wahnfried was the center of life for the Wagner family. It was built according to the wishes of Richard Wagner. After his death it remained the ancestral home of the Wagners. After Siegfried Wagner’s death, his English-born wife Winifred took over and received Adolf Hitler there, among others.

It was damaged during the war and served as a US Army quarters for a few years. Afterwards, it was again inhabited by the Wagners for a few years. Later it became the property of the city of Bayreuth, which made the place accessible as the Richard Wagner Museum.

Villa Wahnfried:

Franz Liszt Museum Bayreuth

In 1993, the city of Bayreuth was able to take over a bequest from the pianist Ernst Burger, who owned a Liszt collection comprising several hundred pieces. It set up a Liszt Museum in the house where Liszt died, next to Villa Wahnfried. Liszt was a guest there several times and occupied the mezzanine floor. Many documents, valuable Liszt portraits, busts and also Liszt’s silent piano, which he often had with him on his many journeys, await the visitor there. The rooms of the museum are arranged chronologically, very informative and the place is absolutely worth visiting.

Liszts deathplace:

A look into the museum:

https://www.bayreuth-tourismus.de/en/places-of-interest/museums/franz-liszt-museum/

Richard Strauss Institute and Museum Garmisch Partenkirchen

In this research site there are also 2 rooms that are open to the public. An overview of his life is offered and headphones invite you to immerse yourself in his work.

http://www.richard-strauss-institut.de/

Richard Strauss Institut:

CEMETERIES AND TOMBS OF FAMOUS MUSICIANS

Richard Wagner: grave at Villa Wahnfried in Bayreuth

From 1874 Bayreuth and the Villa Wahnfried was the center of life for the Wagner family. It was built according to the wishes of Richard Wagner. After the death of Richard Wagner it remained the ancestral home of the Wagners.

Richard Wagner and Cosima Wagner are buried at Villa Wahnfried:

Franz Liszt: tomb in the Stadtfriedhof (city cemetery) Bayreuth

The funeral took place on 3 August, a requiem mass was held on 4 August. At this, Anton Bruckner played his own works and he fantasised about themes from Parsifal. Works by Liszt were not played, apparently Brucker did not know any of his pieces. After Liszt’s death, there was a lengthy tug-of-war over where he was to be buried. The mausoleum was badly damaged during the Second World War and was rebuilt true to the original.

Liszt’s Mausoleum:

Richard Strauss: tomb in the cemetery Garmisch-Partenkirchen

On September 8, 1849, the last great opera composer in the history of music died in his bed after a severe heart attack he had suffered a month earlier.

Richard Strauss’ abdication took place in Munich, his urn lies in the family grave in the Garmisch cemetery.

Richard Strauss’ tomb:

Carl Orff: Gravesite in Andech

Carl Orff was granted a grave on the Holy Mountain in the Sorrowful Chapel of the monastery church at Andechs in 1982 at his personal request.

Carl Orff’s tomb:

Andech:

Max Reger: gravesite in the Waldfriedhof Munich

Max Reger was first buried in Jena and was later moved to Munich, where his widow had later moved. Organ pipes are engraved on his gravestone.

CHURCHES

Mozart-Convent Seeon

This monastery has a history of over a thousand years. It was converted at the beginning of the 19th century and has had a varied history since then. In the meantime it belongs to the Bavarian Free State. Mozart often played here on the organ, which can still be played true to the original.

This place is now a conference venue. Guided tours are offered and you can spend the night in the historic monastery walls.

MONUMENTS AND MISCELLANEOUS

Wagner monument Munich

The Wagner monument was created on a solid block of marble. It was unveiled to mark the composer’s 100th birthday in 1913. Wagner’s widow Cosima refused to take part because she was piqued by the city of Munich, as they were competing with the festival venue Bayreuth with their own performances.

Richard Strauss fountain in Munich

This fountain in honor of the composer in the pedestrian zone was inaugurated in 1962. It contains scenes from the opera “Salome”. Because of the ancient theme and the location in front of a Renaissance building, the artist chose a column shape for the bronze fountain.

Richard Strauss fountain:

Eremitage Bayreuth

The Eremitage is a beautiful 18th century rococo park near the Old Palace. This complex was Liszt’s favorite place in Weimar, maybe the park and the fountains reminded him of Villa d’Este.

Eremitage Bayreuth:

Steingraeber house in Bayreuth

In 1846, Eduard Steingraeber, the son of the founder of the Bayreuth piano manufacturer Steingraeber, became Liszt’s concert piano technician and tutor. His collaboration with the company continued until the end of his life. In 1873, the company produced a rococo-style grand piano for the Rococo Hall, which Liszt often played and therefore got the name “Liszt Grand Piano” and is still in this hall in the Steingraeber House. It is still played at concerts today. For times and dates of tours, concerts, etc., see the producer’s website.

https://www.klavierhaussteingraeber.de/

The Liszt grand piano in the Rococo House:

Liszt at the grand piano:

Mozart oak in Seeon

Not far from the monastery is an old oak tree, the so-called Mozart Oak, under which Mozart is said to have composed.

Mozart oak:

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!